IP Report 2011/V

Patent Law

Reported by Dr. Thomas Friede

In its ruling dated October 18, 2011 the Court of Justice of the European Union (ECJ) had to decide on a referral by the German Federal Supreme Court in a nullity appeal proceedings with respect to a patent of the stem cell researcher Professor Brüstle. The patent relates to neural precursor cells derived from embryonic stem cells, including stem cells produced from the blastocyst stage of human embryos (hES). The claims do not mention the use of embryos for producing the ES cells. As alternative sources stem cells are mentioned which are derived from unfertilized human egg cells, i.e., embryonic germ cells (EGC) and unfertilized eggs in which a cell nucleus from a mature cell has been implanted (“dolly method”). The nullity action against the patent was exclusively based on Section 2 (2) No 3 German Patent Act which is identical to Article 6 (2) lit c Biotech-Directive and stipulates that no patents shall be granted for inventions directed to the use of human embryos for industrial or commercial purposes.

The ECJ ruled that the term “embryo” includes any human egg cell after fertilization and any non-fertilized human egg cell into which either a cell nucleus has been implanted or undergoing parthenogenesis. The ECJ did not decide on the question whether an hES as such represented an embryo (rather, this decision shall be left to the national courts of the Member States).

“Industrial or commercial purposes” cover also scientific research and do not overcome the exclusion from patentability. The exclusion from patentability does not depend on the fact that the prior destruction of human embryos is not contained in the claims. Even if the destruction is not mentioned in the specification at all, exclusion from patentability applies.

The decision of the ECJ does not distinguish between hES inventions which exclusively rely on the destruction of human embryos and hES inventions which can be carried out using hES cell lines. All of them are being excluded from patentability based on the ruling of the ECJ. Furthermore, the ECJ decision does not affect the patentability of iPS (induced pluripotency stem cells) cells which have ES-like pluripotency but which are derived from human reprogrammed adult cells..

Remarks

The decision of the ECJ is especially unfortunate in view of the fact that this year the first clinical trials in Europe for a drug on the basis of hES cells have been approved for the company ACT. The decision may have a negative impact on future research in this field of technology since the research results can no longer be patent protected and the pharmaceutical industry will therefore have a reduced interest in funding hES research in Europe.

Reported by Stefan Burger

When the court issues a notice expressing a legal opinion, the court may only diverge from this opinion in its final decision if the parties are able to discern – based on the course of the oral proceedings, or on a further express notice by the court – that the court is now of an alternate legal opinion that differs from the one originally announced to the parties.

In the decided case, a utility model, concerning a work piece, was challenged with a request for cancellation. In first instance, the German Patent and Trade Mark Office granted the petitioner's request in part, upholding the utility model in limited form as auxiliary requested by the proprietor.

Both parties filed an appeal against this decision at the German Federal Patent Court. With the summons for oral proceedings in this matter, the court also gave the parties notice that “based on the written submissions so far, the court would tend to confirm the decision of the GPTO and that, therefore both appeals should be expected to be rejected”. The same notice was also repeated at the beginning of the oral proceeding. In the decision the Federal Patent Court then cancelled the utility model in its entirety for lack of inventive step.

The proprietor filed a further appeal on the point of law against this decision at the German Federal Supreme Court, arguing that the decision came as a surprise and that it constituted a violation of the right to be heard. The petitioner further argued that further auxiliary requests had already been prepared in order to defend the utility model in more limited form if necessary. However, based on the notice given, these auxiliary requests were deemed unnecessary and, therefore, had not been submitted.

In its decision, the Federal Supreme Court clarified that court notices are intended to serve the purpose of facilitating fair proceedings and reaching the correct decision. Accordingly, the parties have to observe such notices and are expected to address the demands or directions given in such notices. Also, the parties are expected not to elaborate further on points which the court considers unnecessary in its preliminary opinion set forth in the court notice. At the same time, however, the parties may rely on the court notice, irrespective of whether it concerns facts or legal points.

In the decided case, since both parties had been repeatedly informed that both appeals were intended to be rejected, the Federal Supreme Court held that this notice conferred the opinion that the lower instance had decided correctly, at any rate in the result, and therefore the utility model should be expected neither to be cancelled in its entirety, nor upheld in its entirety.

Since there were no indications in the decided case from which the proprietor could have recognized that the Federal Patent Court did not intend to maintain its preliminary legal opinion, and thus the proprietor was allowed to trust that the Federal Patent Court would decide as notified, the Federal Supreme Court held that the Federal Patent Court’s decision, which diverged from the preliminary opinion stated in the notice, violated the petitioner’s right to be heard.

Remarks

This decision is a welcome assurance that parties may in fact rely on a court notice without being surprised in the final decision. Parties can thus concentrate their presentation on the relevant aspects of the case as set out in the notice.

At the same time, however, since such a notice does not bind the court to the legal opinion given, parties are well advised to also be prepared to address any other potential aspects if necessary.

It should also be noted that, although this decision concerns a utility model cancellation, it is also expected to be highly relevant for patent nullity proceedings, where the German Federal Patent Court is generally required by law to issue an advance notice about possible aspects that appear likely to be of importance for a decision, or which serve the purpose of concentrating the oral proceedings on discussing the questions essential for the decision (Section 83 [1] German Patent Act).

Reported by Joachim Mader

A modification of the originally disclosed subject to an “aliud” which would lead to a nullification of the patent is not only given if the patented subject matter is an exclusive “aliud”, but also if the modification relates to a technical aspect which in the originally filed documents was not disclosed as belonging to the invention, either in the concrete embodiments claimed or at least in abstracted form.

According to Section 21 (1) No 4 German Patent Act, a patent has to be revoked if its subject matter extends beyond the content of the patent application as originally filed. According to Section 21 (2) German Patent Act, the patent is to be upheld with a corresponding limitation if the reason for revocation only relates to a part of the patent. On the other hand, according to Section 22 (1) German Patent Act, it is not allowed to amend a granted patent in such a way that the scope of protection thereof is extended in comparison to the version as granted.

In the decided case, German patent DE 43 30 031 C2 was attacked in a nullity proceeding with the argument that claim 1 as granted contained several unallowed amendments. The substantial amendments introduced to claim 1 during the examination proceedings contained several unallowed generalizations of originally disclosed content, several non-disclosed limiting features as well as non-disclosed modifications of originally disclosed features. In the first instance the German Federal Patent Court followed the requests of the nullity plaintiff and revoked the German patent due to unallowed amendments.

In the present decision, the Federal Supreme Court confirmed the earlier case law developed with regard to unallowed amendments in patent claims in German nullity proceedings. In this respect, the Court clarified again that not all kinds of unallowed amendments will inevitably lead to the revocation of a granted German patent. This is in particular true for features which contain (non-disclosed) generalizations of disclosed claim features. Such generalizations can often be corrected by exchanging the generalizing features for the narrower originally disclosed features. Further, also the introduction of non-disclosed features, which lead to a mere limitation of the subject matter are not problematic if care is taken that those non-disclosed limiting features are not taken into account when evaluating the patentability of the claimed subject matter.

Claim 1 (as granted) of the German patent contained undoubtedly several features falling under the above cited two categories of unallowed amendments. Thus, the unallowed amendments introduced into claim 1 of the German patent belonging to these two categories of unallowed amendments would not have necessarily led to a revocation of the patent. However, claim 1 of the German patent also contained a further feature, which was considered by the Federal Supreme Court as an aliud. The Court clarified in this respect that an aliud which leads to a nullification of a granted patent is already given if the additional feature relates to a technical aspect which could not have been derived as belonging to the invention when considering the originally filed documents.

In the present case, the respective feature was directed to a new function of the claimed device, which new function could not be derived from the originally filed documents, neither explicitly, nor in abstracted form, as belonging to the invention. In other words, the objected feature introduced an additional new technical aspect, which was not disclosed in the originally filed documents. The Court further decided, that this problem of granted claim 1 cannot be solved by a corresponding declaration added to the patent, stating that no rights may follow from this objected and unallowed feature, since this would make it too difficult for third parties to evaluate the actual scope of protection of such a patent.

Remarks

With the reported decision the Federal Supreme Court further clarifies the earlier case law developed for unallowed amendments in patent claims specifying in more detail what is considered as a “mere limitation of a claim” compared to an aliud, i.e. a feature that is directed to a different invention. While a mere limitation does not necessarily lead to a revocation of a patent, the presence of an aliud leads inevitably to a revocation due to unallowed amendments.

The decisive difference between a mere limitation and an aliud is that the subject of an aliud is a new technical aspect which cannot be derived from the original documents as belonging to the invention. In contrast thereto, a mere limitation is given if the added feature specifies a teaching for technical action which was, however, disclosed in the originally filed documents as belonging to the invention.

Reported by Stefan Bianchin

If the description of a patent discloses several possibilities to achieve a specific technical effect, but only one of these possibilities is included in the patent claim, an infringement under the doctrine of equivalents can only be assumed if the attacked solution in its specific effects corresponds to the claimed solution and differs in a similar manner as the claimed solution from the non-claimed solution which was disclosed only in the description.

The patent-in-suit related to a method for the manufacturing of a reagent. It was claimed, inter alia, that in a first step a solid phase was epoxidized with a diglycidyl compound, i.e. a compound consisting of two glycidyl groups, providing one epoxy group to the solid phase. In the description, an alternative method for providing one epoxy group to the solid phase was disclosed, namely a binding of a polycarboxylic acid to an amino or mercapto-derivatised organic to the solid phase.

In the attacked method, the epoxy group was obtained in a different way, namely by way of a co-polymerization.

Both the Frankfurt District Court and the Frankfurt Appeal Court considered the attacked method as infringing under the doctrine of equivalents. Both courts mainly based their decisions on the argument that the attacked method provided an alternative solution having the same technical effect to the claimed epoxidation with a diglycidyl compound and that this alternative solution had been obvious to the skilled person at the priority date.

The Federal Supreme Court did not confirm these decisions and remitted the case back to the Frankfurt Appeal Court for further proceedings. In its decision, the Federal Supreme Court referred to its former decision “Occlusion Device” of May 10, 2011 – Case X ZR 16/09, in which it stated that an orientation to the patent claim, which is also a requirement for infringement under the doctrine of equivalents, required that the patent claim, in all of its features, formed the decisive basis for the considerations of the skilled person. If the patent claim made a selective decision between several possibilities for providing a technical effect, the considerations of the skilled person on possible modifications must also be in line with this selective decision. In this respect, only such considerations were therefore oriented to the technical teaching protected by the patent claim, which take account of this selective decision.

As a result, the Federal Supreme Court stated that, in the present case, it has to be determined whether the attacked alternative solution, namely to provide the epoxy group by a co-polymerization, belongs to the claimed solution or to the solution only disclosed in the description of the patent-in-suit. In the latter case, a patent infringement under the doctrine of equivalents is excluded. Only if the alternative solution belongs to the claimed solution, an infringement under the doctrine of equivalents is generally possible. For the further determination as to where the attacked solution belongs, the Federal Supreme Court remitted the case back to the Frankfurt Appeal Court.

Remarks

This decision further clarifies the application of the doctrine of equivalents and its limits in German patent litigation and is therefore of important practical value. It confirms the recent tendency in German case law to hesitate assuming equivalent patent infringement.

Reported by Dr. Rudolf Teschemacher

The European patent system is widely accepted as being user friendly. The revision by the EPC 2000 which entered into force in December 2007 even enlarged the scope of application of further processing which works like the extension of a time limit subject to a fee. However, the reported case shows that there are hidden traps in which the parties may be caught resulting in losses of rights.

The Opposition Division had rejected the opposition. The opponent changed his representative and the new authorized representative filed the notice of appeal. The next day, the EPO informed the new representative by telephone that he had to file an authorization because the previous representative had not informed the EPO that he had ceased to act for the opponent. One month later, the representative faxed a cover letter stating that an authorization signed on behalf of EyeGate Pharma S.A was enclosed. The enclosure confirming that the conduct for the appeal had been transferred to the new representative bears a heading of EyeGate Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Below the signature the name of the signer is repeated in capitals and the function “President and CEO” is added. In the enclosure, there is no reference to the opponent which was EyeGate Pharma S.A. The new authorized representative was entered into the register and further notifications were addressed to him.

Nine months later the registrar of the Board of Appeal issued a communication headed “Inadmissibility of the appeal” with the following text:

“It appears from the file that the appeal in the proceedings mentioned above has the following deficiency:

The required authorization has not been provided. An authorization should be filed for EyeGate Pharma S.A. specifically. It is therefore expected that the appeal will be rejected as inadmissible pursuant to Article 108 in conjunction with Rule 101 (1) EPC. Any observation must be filed within two months from notification of this communication.”

One week before the end of the time limit, an authorization was faxed on EPO Form 1003 signed by the President of EyeGate Pharma S.A. and authorizing the authorized representative to act on behalf of it.

One month later, the proprietor objected to the correctness of the authorization, noting that an original version had not been filed and that the representative’s address was lacking. Another eleven months later the registrar issued a “noting of loss of rights pursuant to Rule 112 (1) EPC” stating that an authorization fulfilling the necessary requirements had not been filed and that the notice of appeal was deemed not to have been filed in accordance with Rule 152 (6) EPC. In reply, the opponent complained that his right to be heard had been violated. In substance, he argued in particular that the EPC did not require that an original of an authorization be filed, that the Board had not invited him to file an original and that the invitation of the Board was misleading since the wrong form had been used.

After having been informed by the registrar that a noting of loss of rights was not a decision, the opponent requested a decision of the Board in accordance with Rule 112 (2) EPC. In the oral proceedings appointed on his request, he inter alia requested to refer to the Enlarged Board of Appeal the point of law whether he had to be invited to file the authorization as an original.

In the decision of the Board of Appeal of November 29, 2010, the noting of loss of rights is confirmed and the appeal is stated as deemed not to have been filed. The Board notes that the procedure to be followed is governed by Rule 152 EPC in conjunction with the decision of the President of the EPO dated July 12, 2007 according to which in case of a change of representative, and where the EPO has not been notified of the termination of the previous representative’s authorization, “the new representative must file, together with the notification of his appointment, an individual authorization (original and one copy) or a reference to a general authorization already on file. If he does not, he shall be requested to do so within a period to be specified by the European Patent Office.”

Since the first authorization had not been signed in the name of the registered party, the opponent had to be invited to file the required authorization. The Board accepts that the form which was used for the invitation was incorrect. Instead of indicating that the sanction for not providing the required authorization would be that any procedural steps taken by the representative shall be deemed not to have been taken (in accordance with Rule 152 [6] EPC), the invitation made reference to Article 108 EPC and Rule 101 (1) EPC and stated that the appeal would be rejected as inadmissible. Nevertheless, the Board is of the opinion that the invitation was clear and that the action called for was unmistakeable. According to the Board, the invitation does not contain any misleading information in this respect. What was required of the new representative was to file an authorization in the name of the opponent. The instruction on the form was unambiguous, it fulfilled the legal obligation under Rule 152 (2) to invite the representative to file a (valid) authorization and it was indeed effective, insofar as it prompted the representative to file a copy of the authorization, albeit by fax. There was no need that the invitation explicitly specified all formal requirements of an authorization to be filed, nor that the representative should repeatedly be given the opportunity to comply with these requirements.

The opponent could not rely on the principle of legitimate expectations requiring that “communications addressed to applicants must be clear and unambiguous, i.e. drafted in such a way as to rule out misunderstanding on the part of the addressee”. It was not necessary that the invitation made a reference to the necessity to file the original version of the authorization. This detail should not have to be spelled out to a professional representative, since he should know this from the above decision of the President. In addition, also the President’s decision concerning the filing by fax and the Guidelines for Examination A-IX, 2.5 stated that authorizations could not be filed by fax.

Considering the further argument of the opponent that he was misled by the recording of the change of representative which made him believe that the filing of the authorization by fax was sufficient and that he could legitimately expect that the EPO would not later on contradict this conduct of proceedings, the Board notes that the registrar may have overlooked the requirement of filing an original and, due to this oversight may have recorded the change. However, this did not help the opponent’s case since the Board refers to decision J 5/02 holding that even if the EPO provided a professional representative with incorrect information, in his capacity as professional representative, he should not have come to the conclusion that the relevant legal provisions are no longer applicable. If he did not realise that the information was incorrect, he was guilty of a fundamentally inexcusable ignorance of the law; if he did realise it was incorrect, he was not misled.

Nor did the Board agree with the opponent’s argument that the principle of good faith as developed by the Enlarged Board of Appeal in

G 2/97 obliged the EPO to issue a warning of the failure to provide an original of the authorization, considering that there was sufficient time for correcting the deficiency. As a principle, the Board states that responsibility for filing a valid authorization cannot be devolved to the Board. Furthermore, the Board does not see a readily identifiable deficiency within the meaning of G 2/97 in the absence of an indication in the accompanying letter that the representative did not intend to file the original within the remaining seven days of the time limit.

The Board did not see any reason to refer a point of law to the Enlarged Board of Appeal since the legal ambiguities on which the opponent relied did not exist in respect of the relevant questions.

Remarks

The decision leaves the reader with some uncomfortable feeling.

The Board appears to have anticipated such a reaction in the last point of its decision reading “the Board is aware that this decision may appear particularly formalistic and disproportionately harsh”. An authorization is a legal instrument and the principal obligation to file it as an original appears to be clear from the law as it stands and the Board is bound to apply this law. However, the question may be asked whether it is justified to maintain this requirement, considering that the person who is entitled to sign an authorization is also entitled to file an application and to sign the request form without a confirmation being required. In the present case, the opponent was resident within the contracting states. Thus, its CEO was entitled to file the notice of appeal by fax himself and to sign it, without a confirmation being necessary under the relevant rules. Therefore, the question is legitimate whether an authorization needs a more qualified form than the acts for which the power is given.

Turning to the peculiarities of the case, there seems to be some imbalance between the consequences of an improper handling of the situation by the EPO and the omission by the representative, and the question arises whether the result achieved was unavoidable. Starting with the form which the Board interpreted as an invitation to the opponent to file the authorization, not only the indicated legal consequence of the deficiency was wrong but the communication as a whole was confusing. The communication was not drafted as an “invitation to remedy a deficiency” or as an “invitation to file an authorization” which would be a usual and proper terminology in such a situation. The announcement that “the appeal will be rejected as inadmissible” gives the impression that such decision is imminent. There is no indication that this course of action can still be changed. In the last sentence, the opponent is given the opportunity to file observations. This may be understood as giving the opponent the opportunity to be heard before the envisaged decision is taken. The sentence “an authorization should be filed” may be understood as an invitation but also as a mere reference to the legal obligation the non-observance of which caused the deficiency which entails the rejection as inadmissible. The confusing text of the communication may have given reason to the addressee to look at the legal consequences indicated. In this respect, he may have found out that Article 108 in conjunction with Rule 101 (1) EPC deals with deficiencies which may not be remedied after the time limits of Article 108 EPC have lapsed. Thus, it may be plausibly argued that the communication did not make clear to the opponent that the authorization could still be filed. The lack of a proper invitation to file the authorization would have as a consequence that the time limit for filing it has not been triggered.

Also the problems related to the principle of legitimate expectations might have been assessed differently. It is true that a representative should know in which form to file an authorization. Hence, an invitation to file it need not address the required details as to form. However, if a communication addresses a deficiency in detail, one might expect that the indications are correct. This might imply that it is not a proper conduct to address one aspect of the deficiency and to ignore the other. If the party is told how to remedy a deficiency, it may assume that it is sufficient to do what it is told to do.

In the present case, the opponent had twice filed an authorization in copy. Thus, when the second authorization was filed it was almost suggesting by itself that the representative did not realise that an original had to be filed and corresponding information to him might have been considered appropriate. In this respect, it should be kept in mind that checking authorizations is a daily task for the registries of the Boards of Appeal. For authorized representatives the situation is somewhat different: In most situations the filing of an authorization is not necessary and in most situations the use of fax without the need to file an original satisfies the formal requirements for acts to be performed in EPO proceedings. This coincides with a deplorable negligence in observing the formal requirements of an appeal which is reflected in numerous decisions of the Boards of Appeal which have to deal with these requirements (see Case Law of the Boards of Appeal, 6th edition 2010, Chapter 7). This negligence is all the more dangerous since further processing is not available for non-observance of the admissibility requirements in Article 108 EPC and re-establishment is totally excluded for the opponent.

In passing, the decision touches a quite different legal problem which would have deserved more attention. In case of change of representative, who is the legitimate representative until a required authorization is filed? The Board appears to assume that this is the old representative because, according to the Board, the new representative should not be registered before. This position may be based on Rule 152 (8) EPC according to which an authorization remains valid until its termination has been communicated to the EPO. However, on the basis of its own position the Board should have addressed all further notifications to the old representative. On the other hand, in accordance with Rule 152 (6) EPC the acts of the new representative are valid and remain valid, unless the authorization is not filed upon invitation. This seems to imply that the new representative is a legitimate representative even before the authorization is filed. And indeed, the decision of the President stipulates that it is the new representative who has to be invited to file the missing authorization. But conducting the proceedings only with him may lead to the consequence that the rights of a party are lost without any information to the previous representative whose authorization is still valid. This seems to be inconsistent with the purpose of Rule 130 (1) in conjunction with Rule 152 (8) EPC. For reasons of legal security, it should be clear who has to be the addressee of any office action.

Trademark Law

Reported by Philipe Kutschke

When assessing protectability of the surface of a product as a trademark, a significant departure from the norm or customs in the sector concerned is sufficient to confer distinctiveness on the mark.

The General Court had confirmed the decision of OHIM’s First Board of Appeal, which had – in accordance with the Examiner’s earlier decision – rejected two Community trademark applications of Freixenet for “sparkling wines” in class 33, comprising the following representations:

The description of these two trademark applications reads as follows: “White polished bottle which when filled with sparkling wine takes on a golden matt appearance similar to a frosted bottle”, respectively “Frosted black matt bottle”. Further to that, Freixenet’s trademark application for the white shaded bottle provided the following disclaimer: “The applicant states that through the mark now being applied for he does not want to obtain restrictive and exclusive protection for the shape of the packaging but for the specific appearance of its surface”, a respective disclaimer was also provided in the trademark application for the black bottle.

The General Court argued that the essential element allowing the relevant consumer to identify the origin of the products was the label affixed to the bottle of sparkling wine rather than the shape of the bottle or its appearance. Thus, the color and matting of the glass of the bottle could not ‘function as a trademark’ for sparkling wine, because it lacked intrinsic distinctiveness. As regards distinctiveness acquired through use (i.e., secondary meaning), the General Court argued that the evidence filed by Freixenet (e.g., market studies) only referred to six of the fifteen Member States that made up the European Union at the time of the filing of the applications for registration (1996) and that Freixenet only filed probative evidence for one Member State.

The Court of Justice disagreed, arguing that the General Court had failed to apply trademark principles as established by the Court’s case law. The General Court had not evaluated whether the signs in question departed significantly from the norm or customs of the relevant sector, but rather concluded that consumers considered labels or other distinctive elements on bottles as indications of commercial origin, and not the appearance of the product or its packaging as such. Thus, the judgment infringed Article 7 (1) (b) CTMR. According to the Court, the assessment made by the General Court would mean that marks consisting of the appearance of the packaging of the product itself and that do not contain an inscription or a word element would be excluded automatically from any protection as a trademark. The same mistake having been made by the Board of Appeal, the Court not only annulled the judgment of the General Court but also the decision of the Board of Appeal.”

Remarks

It rarely happens that the Court of Justice annuls a decision of the General Court, and, thus, the decision is per se remarkable. It becomes even more remarkable when considering that the decision appears to broaden the scope of signs that are protectable under the category of “other” marks. This is good news for inventive companies that do not only rely on words, pictures and shapes to indicate the origin of their products, but who venture beyond these safe terrains. Appearances of products, or of packaging such as bottles or other containers, characterized by their structure or some other specific feature, are registrable as trademarks when these specific features depart significantly from norm or custom in the sector concerned. It is worth pointing out that these same features are also registrable as designs if they are new, as the “departs significantly” may not be much different from “individual character”.

Reported by Dr. Alexander von Mühlendahl, J.D., LL.M.

European Union customs regulation provide for the seizure by customs authorities of goods suspected of infringing intellectual property rights when presented for customs treatment. Previous case law of the ECJ has established that goods in transit do not infringe national or Community intellectual property rights unless the proprietor of the right can show that the goods will necessarily enter the market in the European Union. In view of the apparent conflict between the customs rules and the substantive rules of intellectual property rights a Belgian court of first instance and the Court of Appeal for England and Wales independently presented questions for a preliminary ruling seeking to resolve the issue. In the Belgian case counterfeit Philips electric shavers were seized by customs, and the issue was whether they were subject to sanctions sought by Philips. In the U.K. case, counterfeit Nokia telephones had been seized at Heathrow airport, and the question was whether the seizure should be confirmed or not.

The questions presented were the following:

In the Philips case:

“Does Article 6 (2) (b) of [Regulation No 3295/94] constitute a uniform rule of Community law which must be taken into account by the court of the Member State which (…) has been approached by the holder of an intellectual property right, and does that rule imply that, in making its decision, the court may not take into account the temporary storage status/transit status and must apply the fiction that the goods were manufactured in that same Member State, and must then decide, by applying the law of that Member State, whether those goods infringe the intellectual property right in question?”

In the Nokia case:

“Are non-Community goods bearing a Community trademark which are subject to customs supervision in a Member State and in transit from a non-member State to another non-member State capable of constituting ‘counterfeit goods’ within the meaning of Article 2 (1) (a) of Regulation [No 1383/2003] if there is no evidence to suggest that those goods will be put on the market in the [European Community], either in conformity with a customs procedure or by means of an illicit diversion?”

In the Nokia case, the International Trademark Association had been authorized to intervene before the Court of Appeal and thus was able to present written observations and participate in the oral proceedings before the ECJ, supporting the position of Nokia in favour of customs intervention also against goods in transit.

The ECJ insisted on the requirement of a domestic infringement as a condition of customs intervention or measures against counterfeit goods, thus confirming that goods in transit may not be detained in the European Union.

The ECJ answered the questions as follows:

“Council Regulation (EC) No 3295/94 of December 22, 1994 laying down measures concerning the entry into the Community and the export and re export from the Community of goods infringing certain intellectual property rights, as amended by Council Regulation (EC) No 241/1999 of January 25, 1999, and Council Regulation (EC) No 1383/2003 of July 22, 2003 concerning customs action against goods suspected of infringing certain intellectual property rights and the measures to be taken against goods found to have infringed such rights must be interpreted as meaning that:

- goods coming from a non-member State which are imitations of goods protected in the European Union by a trademark right or copies of goods protected in the European Union by copyright, a related right or a design cannot be classified as ‘counterfeit goods’ or ‘pirated goods’ within the meaning of those regulations merely on the basis of the fact that they are brought into the customs territory of the European Union under a suspensive procedure;

- those goods may, on the other hand, infringe the right in question and therefore be classified as ‘counterfeit goods’ or ‘pirated goods’ where it is proven that they are intended to be put on sale in the European Union, such proof being provided, inter alia, where it turns that the goods have been sold to a customer in the European Union or offered for sale or advertised to consumers in the European Union, or where it is apparent from documents or correspondence concerning the goods that their diversion to European Union consumers is envisaged;

- in order that the authority competent to take a substantive decision may profitably examine whether such proof and the other elements constituting an infringement of the intellectual property right relied upon exist, the customs authority to which an application for action is made must, as soon as there are indications before it giving grounds for suspecting that such an infringement exists, suspend the release of or detain those goods; and

- those indications may include, inter alia, the fact that the destination of the goods is not declared whereas the suspensive procedure requested requires such a declaration, the lack of precise or reliable information as to the identity or address of the manufacturer or consignor of the goods, a lack of cooperation with the customs authorities or the discovery of documents or correspondence concerning the goods in question suggesting that there is liable to be a diversion of those goods to European Union consumers.”

Remarks

The power of customs authorities to seize goods entering the territory of the European Union suspected of infringing intellectual property rights (as well as the power of the various authorities like civil courts to take measures against such goods) requires their placing on the market in the European Union or that their diversion from export is apparent. Thus, we have reached the end of the road in Europe of the fight against counterfeit goods in transit: Seizure now remains in principle possible, but once it is determined that the goods are in transit they must be released.

This result, a major setback in the fight against counterfeit goods, was inevitable because of the “link” of the customs seizure with a domestic infringement. It is in a way the final chapter in the acceptance of the principle of territoriality. The result may appear reasonable when rights exist only in the country of transit, but no rights exist in either the country of origin or the country of destination, but is “near-sighted” when counterfeit goods are involved which are more than likely to be infringing goods also in the country of origin or in the country of destination.

In paragraph 65 of the judgment, we find the following:

“Finally, with regard to goods in respect of which there is no indication as referred to in paragraph 61 of this judgment, but in respect of which there are suspicions of infringement of an intellectual property right in the presumed non-member State of destination, it must be noted that the customs authorities of the Member States where those goods are in external transit are permitted to cooperate, pursuant to Article 69 of the TRIPS Agreement, with the customs authorities of that non-member State with a view to removing those goods from international trade where appropriate.

It appears however highly doubtful that such cooperation may actually lead to the “removal” of counterfeit goods “from international trade where appropriate.”

The recent review of European trademark law undertaken by the Munich Max Planck Institute for Intellectual Property and Competition Law on behalf of the European Commission and published in March 2011 (cf. BARDEHLE PAGENBERG IP Report 2011/II) also analysed the gap in protection resulting from the case law of the ECJ. The Study proposes to amend European trademark law by providing that it amounts to trademark infringement when counterfeit goods in transit would infringe trademark rights in the country of transit and in the country of destination. It remains to be seen whether the European Commission will include such a proposal in the legislative package announced for the spring of 2012.

Reported by Dr. Alexander von Mühlendahl, J.D., LL.M.

Frisdranken Industrie Winters BV fills cans with soft drinks upon order and instruction of various foreign companies into cans provided by the latter. These cans bear marks infringing Red Bull’s trademarks. Frisdranken was held to have infringed Red Bull’s trademarks. Upon appeal to the Dutch Supreme Court (Hoge Raad), the following questions were referred to the ECJ:

(1) (a) Is the mere “filling” of packaging which bears a sign (…) to be regarded as using that sign in the course of trade within the meaning of Article 5 of Directive 89/104, even if that filling takes place as a service provided to and on the instructions of another person, for the purposes of distinguishing that person’s goods?

(b) Does it make any difference to the answer to question 1 (a) if there is an infringement for the purposes of Article 5 (1) (a) or (b)?

(2) If the answer to question 1 (a) is in the affirmative, can using the sign then also be prohibited in the Benelux on the basis of Article 5 of Directive 89/104 if the goods bearing the sign are destined exclusively for export to countries outside [(a)] the Benelux area or [(b)] the Euro-pean Union, and they cannot – except in the undertaking where the filling took place – be seen therein by the public?

(3) If the answer to question 2 (a) or (b) is in the affirmative, what criterion must be used when answering the question whether there has been trademark infringement: should the criterion be the perception of an average consumer who is reasonably well informed and reasonably observant and circumspect in the Benelux or alternatively in the European Union – who then in the given circumstances can only be determined in a fictional or abstract way – or must a different criterion be used in this case, for example, the perception of the consumer in the country to which the goods are exported?

The ECJ analysed the question in view of its case law which has established that in order to constitute infringement the use of the mark must be made by the alleged infringer for the infringer’s goods or services. Frisdranken was providing a service to third parties of filling soft drinks into containers provided by the third party. That activity, according to the ECJ, does not amount to trademark use. The answer to the first question thus was:

Article 5 (1) (b) of First Council Directive 89/104/EEC of December 21, 1988 to approximate the laws of the Member States relating to trademarks must be interpreted as meaning that a service provider who, under an order from and on the instructions of another person, fills packaging which was supplied to it by the other person who, in advance, affixed to it a sign which is identical with, or similar to, a sign protected as a trademark does not itself make use of the sign that is liable to be prohibited under that provision.

Answers to the second and third question were thus not necessary.

Remarks

The judgment of the ECJ, just two weeks after the refusal of the ECJ to approve customs measures when counterfeit goods move through the European Union, must come as a disappointment: A company filling containers which, if placed on the market or being stocked for that purpose would amount to an infringing use, goes “free” when the only activity is the filling of containers provided by third persons, and that on the highly “technical” argument that the filler is not “using” the mark for his own goods and services.

The company ordering the goods may be located abroad and thus difficult to bring to court; the company who produces the containers (cans) may not use the mark for beverages, the maker of the soft drink who fills the drink into supplied containers also does not infringe – that sounds like a perfect approach of producing and thereafter exporting infringing products without fearing liability. The reference of the ECJ, in paragraph 35 of the judgment, to “other rules of law” that may apply –

“35 Inasmuch as such a service provider enables its customers to make use of signs similar to trademarks, its role cannot be assessed under Directive 89/104 but must be examined, if necessary, from the point of view of other rules of law (see, by analogy, Google France and Google, paragraph 57, and L’Oréal and Others, paragraph 104).”

– is not very helpful in this respect either, given the diversity of rules and sanctions available under unfair competition law.

The “gap” in the protection which the present judgment has made apparent stems from the unwillingness or inability of the ECJ to recognize that there are other forms of trademark infringement than straightforward “direct” infringement, variously called “third-party liability” or “contributory” infringement, figures of law well established in the Member States’ law of torts.

Among the submissions made to the ECJ, the European Commission forcefully argued in favour of liability. Perhaps the judgment will be a signal for improving the infringement provi-sions in the Directive and the Community Trade Mark Regulation in the course of the ongoing review of European trademark law.

Reported by Philipe Kutschke

The trademark holder had sued a third party for trademark infringement. This third party filed an invalidation request, arguing that the trademark was devoid of any distinctive character and exclusively served to designate the kind of product (Section 8 [2] No 1, No 2 German Trademark Act). Further to that, it claimed infringement of the principle of clarity of a trademark (Section 8 [1] German Trademark Act). The 3D trademark concerned is International Trademark Registration (Madrid) No 869 586 registered for “Cacao, chocolat, produits de chocolaterie” in class 30. Protection in Germany has been granted as of December 15, 2005, comprising the following representation:

Whereas the German Patent and Trademark Office rejected the invalidation request, the Federal Patent Court, after considering its President’s remarks ordered cancellation of the trademark. Leave to appeal to the Federal Supreme Court was granted.

According to the Federal Patent Court, the representation of the trademark does not reveal the subject of protection clearly enough and thus falls under Section 3 (1), 8 (1) German Trademark Act. The representation as registered does not show how far the trademark holder claims protection for the “third dimension”, because the representation does not provide any three-dimensional elements. According to the Court protection as a registered 3D trademark, in general, will require the filing of various representations showing the sign from different perspectives, if the sign is of a certain complexity. However, for simple signs one representation may suffice, provided that the quality of the representation is acceptable. In this case, the quality was not deemed acceptable, because the representation would not reveal the details of the sign. In particular, shape, orientation in space and stylistic elements remained unclear. Contrary to the trademark proprietor’s statements and the description of the mark, the representation does not necessarily reproduce the picture of a grapevine; rather, the representation may show any number of different items. Also, the description “grapevine” was not clear enough, because it suggests that the trademark holder intended to claim protection for an undefined number of different embodiments of grapevines, whereas German trademark law does not allow protection for a mere conceptional sign.

Remarks

Beware of imprecise trademark filing! In this case, the trademark holder had filed the basic application in France without facing any objections by the French Trademark Office. However, various other national trademark offices covered by the International Registration did not grant protection (Great Britain, Denmark, Sweden). While it may be rare that challenges to protection are made, or objections are raised, based on the quality of the representation of the mark, the present case points to a serious risk when the representations are not sufficiently precise. The precision must be attained in the office of origin, as subsequent changes of the mark as represented with regard to individual designated countries are not allowed. While the trademark proprietor may still appeal to the German Supreme Court, it would seem likely that the Supreme Court, if actually seized, will confirm the decision of the Federal Patent Court.

Problems can be avoided when providing the office where the mark is registered with high quality representations, in case of 3D marks preferably from different perspectives, as drawings or photographs.

Design Law

Reported by Dr. Henning Hartwig

On October 20, 2011, the Court of Justice of the European Union, Europe’s final authority on Community design law, rendered its long-awaited decision in PepsiCo v OHIM (Case C-281/10 P) with the central issue being the manner in which differences or similarities between conflicting designs are established under the Community Design Regulation (“CDR”). The underlying products were small metal plates, also referred to as “rappers”, playthings inserted in product packages, and the validity of the Community design was challenged to be “in conflict with”, i.e., to infringe an earlier Spanish design.

The proceedings before the Court of Justice focused on four legal questions (a fifth question related to an alleged distortion of the facts is not part of this review), namely whether the lower instance, the General Court of the European Union, committed any errors in relation to (i) the constraints on the designer’s freedom (Article 10 [2] CDR), (ii) the concept of the informed user and his level of attention (Article 10 [1] CDR), (iii) the scope of the General Court’s power of review (Article 61 [2] CDR), and (iv) whether it was possible to compare the underlying goods rather than the conflicting designs (Article 10 [1] CDR).

(i) Starting with possible constraints limiting the degree of freedom of the designer in developing the design, the Court of Justice found that assessing such constraints would relate to findings of a factual nature made by the General Court rather than to any legal questions. In fact, PepsiCo did not challenge the facts as being distorted and neither disputed the relevance of the criteria for establishing the designer’s degree of freedom (inter alia, the constraints of the features imposed by the technical function of the product or an element thereof or by statutory requirements applicable to the product). Thus, the Court of Justice, in accordance with settled case law, held the challenge of that assessment as inadmissible.

(ii) Turning to the concept of the informed user and his level of attention, this concept, according to the Court of Justice, first “must be understood as lying somewhere between that of the average consumer, applicable in trademark matters, who need not have any specific knowledge and who, as a rule, makes no direct comparison between the trademarks in conflict, and the sectoral expert, who is an expert with detailed technical expertise”. Consequently and second, such concept had to be understood as “referring, not to a user of average attention, but to a particularly observant one, either because of his personal experience or his extensive knowledge of the sector in question”. Thus, the very nature of the informed user would mean that, when possible, he will make a direct comparison between the designs at issue. However, it cannot be ruled out that such a comparison may be impracticable or uncommon in the sector concerned, in particular because of specific circumstances or the characteristics of the devices which the designs at issue represent.

Third and finally, as regards the informed user’s level of attention, the Court of Justice held that such user, without being a designer or a technical expert, would know “the various designs which exist in the sector concerned, possesses a certain degree of knowledge with regard to the features which those designs normally include, and, as a result of his interest in the products concerned, shows a relatively high degree of attention when he uses them”.

(iii) As regards the scope of the General Court’s power to review the Office’s examination of the differences and similarities between the designs at issue and its determination of whether or not there is a similar overall impression, the Court of Justice found that the in-depth examination of the designs at issue carried out by the General Court, contrary to the position also taken by the Office itself, did not go beyond its power to alter decisions under Article 61 CDR.

(iv) Lastly, and related to whether the Office or the General Court are allowed to base the assessment of the designs in conflict on a comparison of physical samples of actual products rather than only on the designs as disclosed and represented in the contested and in the earlier design registration, the Court of Justice found that such comparison was not mistaken, given that the informed user was different from the ordinary average consumer. The Court added that in the present case the physical comparison was done only to confirm the judgment already reached based on the respective registrations.

Remarks

Only few of the issues touched by the Advocate General (cf. BARDEHLE PAGENBERG IP Report 2011/III) have been addressed by the ECJ in its subsequent ruling. Interestingly, and in line with the Advocate General, the Court seems to allow, by way of an obiter dictum, the imperfect recollection test because the direct, physical comparison of the conflicting designs “may be impracticable or uncommon”, indicating to a more indirect, aka imperfect test. It remains to be seen whether national courts will accept that approach, which seems to be contrary to the past, clear distinction between trademark and design law

Reported by Philipe Kutschke

The German Federal Supreme Court provided further guidance regarding the scope of protection of designs registered in black-and-white.

The claimant was the owner of an International design registration (The Hague), claiming protection inter alia in Germany. The registration shows the following four representations:

The defendant distributed ball pens in various colours, replicating the intermediate portion of the design, some of them comprising further elements, e.g., images, logos and trademarks of third parties. Whereas the Munich District Court granted the asserted claims, the Munich Appeal Court rejected them. The Federal Supreme Court finally reversed and remanded the case.

The Federal Supreme Court confirmed that a design which is registered in black-and-white generally enjoys protection of its shape, independent from any specific colouring. Consequently, it may be successfully enforced against later designs in colour, because when comparing the conflicting designs, the later design has to be taken as if it was also in black-and-white. This would be different only if the challenged design was in contrasting colours which would create an overall different impression from that of the earlier design. The Appeal Court had failed to apply the correct criteria, merely stating that the contrasts produced by the conflicting designs were different without going into any more detail.

In the present case it was disputed whether the design-in-suit consisted of one (i.e., “writing utensil”) or various items (i.e., “writing utensil” and “part of a writing utensil”). The Federal Supreme Court held that, under German design law, the description of a registered design – contrary to the indication of product – influences the scope of protection of a design, and thus concluded that the design-in-suit enjoyed protection for an “intermediate portion of the writing utensil”, i.e., not only for the complete ball pen. Consequently, the Court found that when comparing the conflicting designs the overall impression of the accused design had to be based on this specific portion of the product, i.e., the spiral making up the “intermediate portion” of the pen.

Remarks

It is common ground in trademark law that a trademark registered in black-and-white enjoys protection independent from any specific colouring. Thus, it appears to be appropriate that the Federal Supreme Court extended this concept to design matters. Consequently, prior designs in colour must also be taken into account when judging novelty and individual character. However, taking the infringing design in the “abstract”, i.e., discounting the presence of colours, has its limits. The Court points out that an infringing design with contrasting colours may create an impression which is overall different from that of the allegedly infringed design. In this regards as well, no fixed rules apply – the overall impression must be assessed on the basis of the facts in each case.

Reported by Dr. Henning Hartwig

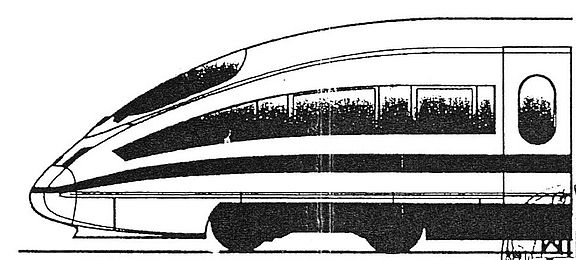

In its most recent design law decision, the German Federal Supreme Court took the opportunity to clarify and refine some essential standards of how to determine infringement of a design. The declaratory judgment defendant, the German railway company “Deutsche Bahn”, owner of two designs covering the outer appearance of the current ICE 3 train, charged the claimant for alleged infringement. The claimant – a research facility in the field of rail vehicle technology and responsible, on behalf of the defendant, for developing a testing facility for sets of wheels for the ICE 1 train – had advertised its services in a catalogue and shown an ICE 3 train for these purposes.

The Federal Supreme Court, first, confirmed a broad construction of infringing acts and among them also counted the two dimensional rendition of a design in the form of a catalogue illustration (the two-dimensional rendering of a three-dimensional design is not explicitly included in the list of infringing acts in Section 38 [1] German Designs Act and Article 19 [1] Community Design Regulation).

Second, the Court confirmed substantial principles for the assessment of a design’s scope of protection (cf. Section 38 [2] German Designs Act and Article 10 Community Design Regulation). In fact, there is a clear interaction between the degree of freedom of the designer in developing his design and the latter’s scope of protection, with the consequence that the scope largely depends on the design’s distance from the existing design corpus at the time the design was made. In the case at hand, the lower instances neither defined the overall impression of the design-in-suit and the infringing design, nor defined the design-in-suit’s scope of protection. In this respect not only similarities, but also differences of the designs are to be taken into consideration, according to the Supreme Court.

Interestingly and third, pursuant to the Court’s finding, the objected design illustration showed, different from the asserted design, the distinctive logo “ICE” (see below). The appearance of this logo, said the Court, must be taken into account when determining the accused design’s overall impression:

Finally and fourth, the Supreme Court denied that the claimant would be entitled to rely on limitations of the rights conferred by a Community design, pursuant to Section 40 No. 1 German Designs Act and Article 20 (1) lit c Community Design Regulation, i.e., that the accused acts were done “for the purpose of making citations or of teaching, provided that such acts are compatible with fair trade practice and do not unduly prejudice the normal exploitation of the design, and that mention is made of the source”. Inter alia, the Court found that “for the purpose of making citations” would require an “inner connection between the reproduced design and the thoughts of the person making the citation” and “the reproduction of the design served as a reference or as a basis for discussing the person’s own citations”. Such inner connection was lacking in the case at hand, simply because the illustration of the ICE 3 train did not serve as support for the claimant’s own citations but rather exclusively served its marketing interests. Furthermore, the claimant had only developed a testing facility for sets of wheels for the ICE 1 train but not for the ICE 3 train.

Remarks

The Supreme Court itself, in the “headnote” attributed by the court, highlighted the aspect of “citation” – and, indeed, this is the first case to our knowledge that has dealt with that particular issue – well established in copyright law – in design law. Somewhat puzzling and perhaps even more interesting because of its practical implications is the Court’s statement that the mark ICE shown on the contested design (a mark, it should be pointed out, also owned by Deutsche Bahn) must be considered when determining the contested design’s overall impression. While it remains unclear what specific importance or relative weight the Court would attach to that fact, this statement seems nonetheless potentially ground-breaking. This is because up until now, it appeared to be common ground that the mere addition of a trademark to a design would not produce a different overall impression. For example, the General Court of the European Union took the view that the “pre-sence of the SYMBICORT mark in the SYMBICORT design does not amount to a significant difference” (cf. BARDEHLE PAGENBERG IP Report 2011/III). Thus, further clarification seems to be necessary and would be welcome.

Plant Variety Law

Reported by Dr. Alexander von Mühlendahl, J.D., LL.M.

The proprietor of Community plant variety rights to certain apple trees producing apples marketed under the trademark “Kanzi” brought an action for infringement of the exclusive rights against two persons selling “Kanzi” apples who claimed to be entitled to such sales as having obtained the apple trees from a licensee of the right holder. The right holder argued that the licensee had sold the plants in breach of the license agreement. The Belgian Supreme Court referred the following questions to the ECJ:

1. Should Article 94 of Council Regulation (EC) No 2100/94 of July 27, 1994 on Community plant variety rights, as amended by Council Regulation (EC) No 873/2004 of April 29, 2004, read in conjunction with Articles 11 (1), 13 (1) to (3), 16, 27 and 104 thereof be interpreted in such a way that the holder or the person enjoying the right of exploitation may bring an action for infringement against anyone who effects acts in respect of material which was sold or disposed of to him by a licensee of the right of exploitation if the limitations in the licensing contract between the licensee and the holder of the Community plant variety right that were stipulated to apply in the event of the sale of that material were not respected?

2. If so, is it of significance for the assessment of the infringement that the person effecting the aforementioned act is aware or is deemed to be aware of the limitations thus imposed in the said licensing contract?

The ECJ, in the absence of detailed information about the content of the license agreement, the breach of which was alleged to have occurred, limited the analysis to the general question of the relationship between exhaustion of rights, which occurs upon the sale of a product and prevents restrictions on further marketing, and the right to enforce plant variety rights when products have been obtained in breach of a license agreement.

The ECJ answered the questions as follows:

1. In circumstances such as those at issue in the main proceedings, Article 94 of Council Regulation (EC) No 2100/94 of July 27, 1994 on Community plant variety rights, as amended by Council Regulation (EC) No 873/2004 of April 29, 2004, read in conjunction with Articles

11 (1), 13 (1) to (3), 16, 27 and 104 thereof, must be interpreted as meaning that the holder or the person enjoying the right of exploitation may bring an action for infringement against a third party which has obtained material through another person enjoying the right of exploitation who has contravened the conditions or limitations set out in the licensing contract that that other person concluded at an earlier stage with the holder to the extent that the conditions or limitations in question relate directly to the essential features of the Community plant variety right concerned. It is for the referring court to make that assessment.

2. It is of no significance for the assessment of the infringement that the third party which effected the acts on the material sold or disposed of was aware or was deemed to be aware of the conditions or limitations imposed in the licensing contract.

Remarks

Plant variety cases have rarely reached the ECJ, and this appears to be the first case relating to infringement of Community plant variety rights. The specific issue was the conflict between exhaustion of rights and the exercise of the exclusive rights conferred by a Community plant variety right.

Council Regulation (EC) No 2100/94 of July 27, 1994 on Community plant variety rights (...), as amended by Council Regulation (EC) No 873/2004 of April 29, 2004, the Community Plant Variety Right Regulation (CPVR), provides for exhaustion of rights, subject to certain limita-tions. Article 16 CPVR provides as follows:

The Community plant variety right shall not extend to acts concerning any material of the protected variety, or of a variety covered by the provisions of Article 13 (5), which has been disposed of to others by the holder or with his consent, in any part of the Community, or any material derived from the said material, unless such acts:

(a) involve further propagation of the variety in question, except where such propagation was intended when the material was disposed of; or

(b) involve an export of variety constituents into a third country which does not protect varieties of the plant genus or species to which the variety belongs, except where the exported material is for final consumption purposes.

As regards licenses, these are provided for in Article 27 CPVR as follows:

1. Community plant variety rights may form in full or in part the subject of contractually granted exploitation rights. Exploitation rights may be exclusive or non-exclusive.

2. The holder may invoke the rights conferred by the Community plant variety right against a person enjoying the right of exploitation who contravenes any of the conditions or limitations attached to his exploitation right pursuant to paragraph 1.

Compared to Community trademark law, which is dealt with at some length in the decision, the breaches of licensing agreements which may be enforced by infringement actions under the CPVR appear much broader: In Community trademark law the infringement sanction is available only to specific breaches, notably breach of quality standards (Article 22 [2] CTMR).

The Court, without going into details and leaving the decision to the national court, considers only those breaches as relevant which “(…) relate directly to the essential features of the Community plant variety right concerned”.

As a matter of Community law, it appears regrettable that the Court refused to explain in some detail, or even generally, what the “essential features” of the Community plant variety right may be. “Essential features” sounds much like the famous dichotomy between “existence” or “substance” or “specific subject matter” of intellectual property rights and their exercise, analysed under free movement of goods or competition law principles. But while we have been reminded of the specific subject matter of trademarks, which recently have been augmented by the so-called advertising or communication function and the investment function, we so far fail to have any indication what these “features” may be in case of plant variety rights.