IP Report 2011/I

Patent Law

Reported by Dr. Christopher Brückner

The Court of Justice of the European Union decided that a Supplementary Protection Certificate for plant protection products which had obtained a provisional marketing authorisation can be granted, thereby safeguarding continuation of the present practice.

The German Patent Court has asked the Court of Justice of the European Union on the interpretation of Article 3 (1) (b) of Council Regulation 1610/96 regarding the creation of a Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC) for plant protection products. The main question in this case was whether an SPC can be granted already with receipt of a provisional marketing approval in the sense of Article 8 paragraph 1 of Directive 91/414/EEC, or only with receipt of a final approval in the sense of Article 4 of this Directive.

Article 3 lit b of Regulation 1610/69 states that an SPC shall be granted if in the Member State in which the application referred to in Article 7 is submitted, on the date of that application, a valid authorization to place the product on the market as a plant protection product has been granted in accordance with Article 4 of Directive 91/414/EEC or an equivalent provision of national law.

Article 13 of the Regulation states that, for calculation of the term of the SPC, a provisional marketing approval may only be considered when a final approval follows immediately. In the present case, the defendant had filed an application for an SPC based on a basic patent claiming a herbicide compound and on a provisional marketing approval. Five years later, a final marketing approval was granted.

The German Patent and Trademark Office had refused the grant of an SPC based on the provisional marketing approval. Following an appeal of the defendant, the SPC was granted. For calculation of the term of this SPC the provisional marketing approval was used.

The claimant had started a nullity suit against this SPC based on the argument that the underlying marketing approval did not fulfil the requirements of Article 3 lit b of Regulation 1610/96.

The German Federal Patent Court had doubts regarding the interpretation of Article 3 lit b of Regulation 1610/96 and therefore submitted the question at issue immediately to the Court of Justice of the European Union:

“Is the existence of an authorization to place the product on the market in accordance with Article 4 of Directive 91/414/EEC exclusively decisive for the application of Article 3 (1) b of the Regulation or can a certificate also be granted based on an authorization to place the product on the market in accordance with Article 8 (1) of Directive 91/414/EEC?”

In the procedure before the Court of Justice of the European Union, the defendant underlined the economic importance of the question. Until that time, it was common practice of the German Patent and Trademark Office to grant an SPC based on provisional marketing approvals according to Guideline 91/414. If this practice was to prove unjustified, a lot of existing SPCs would be void and the resulting damage for the industry would be enormous. A restriction of Article 3 lit b of Regulation 1610/69 would be contrary to the intention of this regulation, especially because the process of granting a marketing authorization often takes a long time, in some cases even until the underlying patent has elapsed. Marketing authorization according to Article 4 and Article 8 Section 1 lit b would be equivalents in effect.

The claimant stated that the wording of Article 3 Section 1 lit b clearly spoke against the granting of an SPC for a product for which a provisional marketing authorization had been obtained. Such provisional marketing authorization was not mentioned in Article 3 Section 1 lit b. The systematic setting of Regulation 1610/96 would clearly speak against this as well.

The Court of Justice of the European Union answered the referred question of law as follows:

“Article 3 (1) (b) of Regulation (EC) 1610/96 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 July 1996 concerning the creation of a Supplementary Protection Certificate for plant protection products must be interpreted as not precluding a Supplementary Protection Certificate from being issued for a plant protection product in respect of which a valid marketing authorization has been granted pursuant to Article 8 (1) Council Directive 91/414/EEC of 15 July 1991 concerning the placing of plant protection products on the market, as amended by Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 February 2005”, i.e. a provisional marketing authorization suffices.

Reported by Joachim Mader

A feature which was not disclosed as belonging to the invention in the originally filed documents and the deletion of which would lead to an extension of the scope of protection may remain in the patent claim if the introduction of this feature leads to a limitation in view of the content of the application.

A limitation in this sense is given if the added feature specifies a directive for technical actions which is disclosed as belonging to the invention in the originally filed documents.

In such cases it is generally not necessary to include a corresponding hint in the patent specification that no rights may derive from the addition of this feature.

According to Section 21 (1) No 4 PatG (German Patent Act) a patent has to be revoked, if its subject matter extends beyond the content of the patent application as originally filed. According to Section 21 (2) PatG, the patent is to be upheld with a corresponding limitation if the reason for revocation only relates to a part of the patent. On the other hand, according to Section 22 (1) PatG, it is not allowed to amend a granted patent in such a way that the scope of protection thereof is extended in comparison to the version as granted.

In the decided case, German patent 195 49 795 was attacked in opposition proceedings inter alia with the argument that claim 1 as granted contained several unallowed amendments. In the course of the opposition appeal proceedings, claim 1 as granted was upheld in amended form and an additional hint was included in the pa-tent specification that certain features of claim 1 contain unallowed amendments to clarify that the features in question may not be considered for the discussion of patentability.

The German Federal Patent Court allowed the appeal to the Federal Supreme Court to answer in particular the questions if and under which circumstances a hint may be included in the description of the patent clarifying that certain parts of the patent claim represent an unallowed amendment, and to relieve the patent from the legal effects of such unallowed amendments. In the opinion of the Patent Court, these questions are of particular importance in view of the case law of the Enlarged Board of Appeal of the European Patent Office which does not consider the solution preferred by the German case law (i.e. adding a hint in the specification) as being in accordance with the regulations of the European Patent Convention.

The appeal of the opponent before the Federal Supreme Court was successful and the case was referred back to the Patent Court. According to the ruling of the Federal Supreme Court, the Patent Court did not sufficiently evaluate whether the illegitimately introduced features of the claim represent a mere limitation compared to the content of the application as originally filed, or whether these features represent a different invention, a so-called “aliud”. The Federal Supreme Court affirmed the legal practice (BGH, GRUR 2001, 140 – Zeittelegramm) that an originally non-disclosed feature may remain in the patent claim if it results in the limitation of the subject matter of the application.

If the originally non-disclosed feature is not just a limitation but is indeed directed to a different invention, i.e. if the patent protects something which represents an “aliud” in view of the originally filed documents, then this feature must not remain in the claim. In this regard, the Federal Supreme Court clarified the meaning of the expression “limitation”. According to the Federal Supreme Court, a limitation is given if the added feature specifies a teaching for technical action, which in the originally filed documents was disclosed as being part of the invention. In such a case, the Supreme Court further ruled, a corresponding hint in the description of the patent is not absolutely necessary, although it is generally not objectionable.

The Federal Supreme Court also commented on the corresponding situation before the European Patent Office. The Federal Supreme Court acknowledged that the German practice may lead to deviating results, at least in the case that a non-disclosed feature represents only a limitation when compared to the practice of the European Patent Office. However, the Supreme Court did not follow the ruling of the Enlarged Board of Appeal of the European Patent Office since the wording of Section 21 (1) PatG does not contain any explicit regulation for cases in which the necessary deletion of an originally non-disclosed feature from a claim would create a new reason for revocation of an unallowed extension of the scope of protection of a granted claim.

Remarks

With the reported decision the Federal Supreme Court clarifies that the case law developed for unallowed amendments in patent claims in German nullity proceedings is also applicable for German opposition proceedings. Thus, an originally non-disclosed feature may remain in a patent claim if the same represents a mere limitation compared to the originally filed subject matter. In this respect, the Supreme Court now clarifies that a limitation in this sense is present if the added feature specifies a teaching for technical action which was disclosed in the originally filed documents as belonging to the invention.

Reported by Thomas Schachl, LL.M.

The plaintiff sued the defendant for literal patent infringement. No facts or arguments were filed by the plaintiff to substantiate patent infringement by equivalent means.

The District Court in first instance and the Appeal Court in second instance granted the requested injunction on the basis of literal patent infringement. Upon further appeal, the Federal Supreme Court denied literal patent infringement in third instance and therefore had to decide whether it had to consider the arguments of the plaintiff based on patent infringement by equivalent means although these arguments were only filed with the Federal Supreme Court in third instance.

The Federal Supreme Court decided that arguments related to infringement by equivalent means must be considered by the Federal Supreme Court in third instance if the plaintiff can show that he would have been able to file related facts and arguments previously with the Appeal Court (second instance court).

With this decision, the Federal Supreme Court confirms, once again, that infringement by equivalent means is accepted in German patent litigation. It further confirms the established German case law according to which an injunction based on patent infringement by equivalent means can only be granted by a court if a related explicit request has been submitted including corresponding facts and evidence if necessary. Finally, it is now clarified that such a request including related facts and evidence may also be filed for the first time with the Federal Supreme Court in the third instance, at least in a scenario such as in the decided case, in which the plaintiff may have had no reason to argue equivalent infringement in view of the foregoing decisions of the instance courts having found literal infringement.

Remarks

However, in view of the timing and increasing chances of success, it is clearly not advisable to postpone filing an (auxiliary) request based on infringement by equivalent means for the first time with the Federal Supreme Court. Rather, it is usually advisable to file such a request at an early stage of the first instance, if the risk of literal infringement needs to be covered.

Reported by Dr. Thomas Gniadek

As regards an interpretation of the patent claim according to the literal sense, the functional interpretation may not result in reducing the content of spatially-physically defined features to their mere function such that the interpretation is no longer in line with the feature’s spatial-physical arrangement. As regards an interpretation of the patent claim according to the doctrine of equivalence, the person skilled in the art must find a hint within the patent that the differing embodiment with its modified means can be considered as a solution which is equivalent to the solution according to the literal sense.

In the present case, the plaintiff accused the defendant of infringing claim 1 of the European Patent EP 1 544 389 B1 (in the following “patent-in-suit”) concerning an actuation device for an anti-panic locking device. With respect to the realization of claim 1, the only disputed feature was feature k claiming that “cover rods are mounted at the guide levers” (emphasis added). The District Court held that claim 1 was infringed because, according to a general technical understanding, a mounting or bearing was a functional joint of members transferring motions, and claim 1 covered a direct and an indirect mounting or bearing. The Appeal Court overruled this decision and held that with the attacked embodiment the cover rods were not mounted at the guide levers neither in a literal sense nor under the doctrine of equivalence.

The present decision concerns the interpretation of the extent of protection of patent claims comprising features that are defined “spatially- physically” – meaning features that define the concrete position or physical structure of a member within the protected device. According to Article 69 (1) EPC and Section 14 German Patent Act, the extent of protection is determined by the terms of the claim, whereas the patent’s description and drawings shall be used to interpret the claim wording. According to Article 1 of the Protocol on the interpretation of Article 69 EPC, the extent of protection is neither restricted to the strict, literal meaning of the wording of the claims nor do the claims serve only as a guideline for the interpretation. Hence, if claims and description differ, the claims are decisive. However, description and drawings need to be consulted to determine what the literal meaning of the wording according to the entire content of the patent is.

Further, under German Patent Law it is established that a technical term has to be interpreted in view of the technical purpose of the feature (“functional interpretation”). Moreover, the general technical meaning of a term is not decisive. Instead, the patent constitutes “its own dictionary”. Thus, the term’s specific meaning in view of the entire content of the patent is relevant. Such functional approach may either result in a claim construction which is narrower than the strict wording according to the term’s general meaning – not “below” the correctly interpreted wording – or may result in a claim construction that is wider than the strict wording according to the term’s general meaning.

In its reasoning, the Appeal Court outlined that when applying the functional approach to features that are defined spatially-physically, the content of such spatial-physical features might not be reduced to their mere function such that the interpretation was no longer in line with the feature’s spatial-physical arrangement. At hand, the Appeal Court concluded that the patent opted for a mounting of the cover rods at the guide levers. Therefore, a mounting at any other member of the embodiment did not constitute a literal realization of the patent claim – even if it served an equivalent purpose.

Moreover, the Appeal Court ruled that in the case at hand there was no infringement even under the doctrine of equivalence. In a nutshell, patent infringement under the doctrine of equivalence requires (1) that the modified means achieve the same technical effect as the means according to the literal sense, (2) that the modified means are obvious to the person skilled in the art at the priority date, and (3) that the person skilled in the art considers the modified means as a solution which is – oriented to the literal meaning of the claims – equivalent to the means according to the literal sense.

In its reasoning, the Appeal Court specified the third requirement of the doctrine of equivalence and pointed out that, with respect to the necessary orientation to the literal meaning of the claims, the person skilled in the art must find some hint or stimulus for the modified means within the patent to be able to consider these means as equivalent. The Appeal Court concluded that there was no hint for mounting the cover rods at any other member of the attacked embodiment in the patent-in-suit. Instead, claim 1 specifically required to mount the cover rods at the guide levers. Hence, there was no infringement by equivalent means.

Remarks

As regards the first aspect of the reported decision – the literal interpretation of spatially-physically defined features –, the Appeal Court determines what is widely accepted. If the content of such features was reduced to the mere function such that it exceeds the spatial-physical definition of the feature, mere equivalent means would fall within the literal scope of the patent. In this respect, if the claim requires a “screw”, a screw is meant – and not a detachable joint fulfilling an equivalent purpose (cf. Meier-Beck, GRUR 2003, 905, 907).

The importance of the reported decision follows from a combination of this first aspect with the second aspect of the decision, according to which the modified means are only equivalent to the teaching protected by the claims in a literal sense if the person skilled in the art may find some hint for the modified means within the patent.

The consequence for patent applicants is to carefully consider whether a claim limitation by spatially-physically defined features is meaningful in view of any possible design-around. If the spatial-physical arrangement is not strictly fulfilled, a design-around may easily fall outside the literal scope of protection. And, with respect to spatially-physically defined features, there does not seem to be much room left for alternatively arguing infringement under the doctrine of equivalence, except for cases in which there is a hint in the patent that suggests that the modified means are equivalent given the clear spatial-physical definition of the feature within the claim.

Reported by Dr. Stefan V. Steinbrener

A decision as referred to in Rule 111 (2) EPC should in principle be complete and self-contained and be comprehensible.

The application relating to a method for preparing and ultrasonically testing a thermal-spray coated article was refused by the Examining Division with a decision “on the file as it stands”. After three substantive communications and a summons to oral proceedings requested by the applicant as an auxiliary measure, the applicant had withdrawn its request for oral proceedings and had requested an appealable written decision in accordance with the current state of the file.

The Examining Division then issued a summary decision reading:

“In the communication(s) dated 14.12.2005, 16.07.2007, 19.06.2008 the applicant was informed that the application does not meet the requirements of the European Patent Convention. The applicant was also informed of the reasons therein.

The applicant filed no comments or amendments in reply to the latest communication, but requested a decision according to the state of the file by a letter received in due time on 17.11.2008.

The European patent application is therefore refused on the basis of Article 97(2) EPC.”

When appealed, Board 3.2.07 considered the decision of the Examining Division to be deficient in that it was not reasoned as required by Rule 111 (2) EPC.

In arriving at this conclusion, the Board scrutinised the Division's communications and the applicant's reactions to them in detail. The Board found that the communications only contained allegations of lack of clarity and/or novelty or inventive step without giving any comprehensible reasoning, although the applicant had limited the claims twice and submitted arguments in support of the amendments made.

The Board thus held that it was evident that the impugned decision fell short of revealing the reasons on which the Division's objections were based. Furthermore, contrary to what was stated in the second and third communications (“the applicant's explanations … have been carefully considered”), it was apparent that the Examining Division ignored all the applicant's arguments since these communications and therefore the decision were silent on this topic. Consequently, the impugned decision was also not reasoned in that respect.

In the Board's view, it was also evident that the Examining Division, when issuing the impugned decision, did not follow the Guidelines for Examination in the European Patent Office, according to which the reasoning must contain in logical sequence those arguments which justify the order. Furthermore, the reasoning should be complete and independently comprehensible, and the reasoning should contain important facts and arguments which speak against the decision (see the Guidelines, E-X, 5). The latter means that the decision should address the arguments of the losing party (not in the least to also comply with the right to be heard).

Moreover, even though claim 1 of the three sets of claims had been amended twice by incorporating further features so that the subject-matter of claim 1 of the three different requests had been substantially restricted, the impugned decision referred to all three substantive communications.

This meant that it was left to the Board to construct the applicable reasons by having to “mosaic” the various arguments from the file, or that it left the Board in doubt as to which arguments apply to which claim version. This approach did not meet the requirement of a “reasoned” decision in accordance with Rule 111(2) EPC.

To be able to benefit from a “decision on the state of the file as it stands” an Examining Division should make sure that its communications were well-structured, dealt sufficiently with the counterarguments put forward and provided reasoned support for what it alleged.

The lack of reasoning in a decision was a substantial procedural violation since it resulted in the appellant being deprived of any reasoning which it could properly address in appeal and the Board being unable to properly examine the reasons why the Examining Division came to the conclusions of lack of novelty and/or lack of inventive step, or lack of clarity. The Board therefore considered it appropriate to set aside the decision under appeal for this reason alone and to remit the case to the department of first instance for further prosecution. The appeal fee was reimbursed.

Remarks

Applicants not uncommonly ask for a decision in accordance with the state of the file when they get the impression that the outcome of proceedings before the Examining Division does not look promising. Under these circumstances, a fast transition to the appeal phase might appear preferable over investing more time and money in a useless exercise. It goes without saying that such requests redound to the benefit of both sides since straightforward summary decisions will normally not inconvenience the Examining Division.

However, in accordance with decision T 1442/09, an Examining Division may only be able to positively respond to a request for deciding as the file stands if it has done its job properly in the past by comprehensibly setting out the reasons for not allowing the latest version of the claims and dealing with the applicant's counterarguments. If this is not the case, any preceding deficiencies will not be remedied, and the Examining Division will not be cleared of a procedural violation by simply relying on the applicant's request. Such an approach would not take account of the requirements of Rule 111(2) EPC stipulating that “decisions of the European Patent Office which are open to appeal shall be reasoned”, which is a prerequisite for the examination of an appeal since the function of appeal proceedings is to give a judicial decision upon the correctness of a separate earlier decision taken by a department of first instance.

On the other hand, issuing as a response to such a request a fully reasoned decision dealing for the first time with all necessary aspects must be seen as an infringement of the right to be heard unless it might be assumed that by asking for a decision according to the state of the file the applicant has waived this right, which however has been denied by case law (see e.g. T 1309/05-3.4.02). Hence, the least problematic option for the Examining Division would be another communication completing its reasoning before issuing a decision on the file as it stands. This may not be welcomed by examiners, but would in the end also substantively improve the overall efficiency of the combined examining and appeal proceedings for all those involved by avoiding an imminent remittal.

T 1442/09 is not an isolated decision since various Boards have already expressed their concerns about such formal summary decisions, in particular if they refer back to multiple communications without taking account of amendments to the claims made in the meantime (see e.g. the decisions cited in T 1442/09 and further decisions cited in these decisions). It must therefore be concluded that decisions in accordance with the state of the file are only possible under the narrow circumstances resulting from Rule 111(2) EPC, and the advice specifically given to applicants in this respect in Guidelines, E-X, 4.4 would hardly appear to hit the point.

Reported by Dr. Rudolf Teschemacher

A non-microbiological process for the production of plants containing the steps of sexually crossing the whole genome of plants and subsequently selecting plants which contains a step of technical nature is

- excluded as an “essentially biological process” if the technical step serves to assist the steps of sexually crossing or selecting;

- not excluded as an “essentially biological process” if the technical step itself introduces a trait into the genome or modifies a trait in the genome, so that the introduction or modification is not the result of the mixing of the genes of the plants chosen for crossing.

In the context of examining the exclusion from patentability

- technical steps performed before or after crossing and selecting have to be ignored;

- the importance of the technical step for the otherwise biological process is irrelevant.

The inventions underlying the referring decisions T 83/05 (OJ EPO 2007, 644) and T 1242/06 (OJ EPO 2008, 523) concern methods of producing vegetables with desired properties, the methods comprising steps of crossing and selection. In the Broccoli case molecular markers are used for selecting appropriate candidates; in the Tomato case the fruit remains on the vine past the point of normal ripening in order to be screened for desired properties.

The main reason for Technical Board of Appeal 3.3.04 for referring the point of law to the Enlarged Board of Appeal (EBA) was a possible conflict of Rule 26(5) EPC, stipulating that “a process for the production of plants (…) is essentially biological if it consists entirely of natural phenomena such as crossing or selection” (emphasis added), with Article 53 lit b EPC, excluding from patentability essentially biological processes for the production of plants, as interpreted in the past in the case law of the Boards of Appeal.

As to the interpretation of Rule 26 (5) EPC which is identical to Article 2 (2) of the Biotech Directive, the EBA states that the provision is ambiguous if not contradictory since crossing and selection are given as examples of natural phenomena, whereas systematic crossing and selection are in fact implemented by means of human intervention. An extensive examination of the legislative history of the Biotech Directive only leads to the result that the intentions of the legislator remain unclear and that the contradiction between the terms of the provision cannot be further clarified.

In the absence of any further guidance, the EBA interprets the provision on its own authority, starting with interpreting the terms “essentially biological processes for the production of plants” in Article 53 lit b EPC. From the term “essentially” it is deduced that an interpretation of the provision is excluded according to which the mere presence of one biological feature in a process automatically confers an essentially biological character on the process as a whole. Also the converse approach is ruled out from the outset, with the consequence that not any technical feature, irrespective of its importance for an otherwise biological process, can be sufficient for escaping the exclusion. In this respect, the approach for determining the technical character of computer-implemented inventions as accepted in G 3/08 (not yet in OJ EPO) is distinguished.

Turning to approaches taken in the previous case law, the EBA takes the position that criteria linking the decision on the criterion “essentially biological” to the state of the art are not appropriate. The considerations relevant for patentability must not be conflated with those for novelty and inventive step for reasons of legal certainty. The standards to be applied cannot change with every piece of prior art. Furthermore, plant breeders have always made use of technical means to achieve the desired results, and modern plant breeding technologies make wide use of advanced technologies in the context of the steps of crossing, growing and selection.

Examining the purpose of Article 53 lit b EPC on the basis of the historical documentation of the EPC 2000, the EPC 1973 and the Strasbourg Patent Convention of 1963, the EBA finds that the legislator’s intention was to exclude from patentability the kind of plant breeding processes which were the conventional methods of that time which were characterised by the fact that the traits of the plants resulting from crossing were determined by the underlying natural phenomenon of meiosis, i.e. the breeding result was achieved by the breeder’s selection of plants having the desired traits. Whereas the legislator regarded technical devices or means to be used in plant breeding processes as patentable in themselves, the protection should not be extended to the biological process in which they are used. The enormous development of the technical means to influence crossing and selection is not sufficient to render the legislator’s decision unjustified. As a result, the EBA concludes that the provision of a technical step in a process which is based on the sexual crossing of plants and on subsequent selection does not cause the claimed invention to escape the exclusion if that step only serves to perform the process steps of the breeding process.

However, if an additional technical step by itself introduces a trait into the genome or modifies a trait in the genome of the plant, the process leaves the realm of plant breeding and thus is not excluded from patentability. In order to exclude circumvention, this applies only if the additional step is performed within the steps of sexually crossing and selection, independently from their number of repetitions. Any additional steps performed before or after crossing and selection have to be ignored when determining whether a process is excluded under Article 53 lit b EPC.

On the basis of its considerations, the EBA answered the referred questions of law as follows:

“1. A non-microbiological process for the production of plants which contains or consists of the steps of sexually crossing the whole genomes of plants and of subsequently selecting plants is in principle excluded from patentability as being “essentially biological” within the meaning of Article 53 lit b EPC.

2. Such a process does not escape the exclusion of Article 53 lit b EPC merely because it contains, as a further step or as part of any of the steps of crossing and selection, a step of a technical nature which serves to enable or assist the performance of the steps of sexually crossing the whole genomes of plants or of subsequently selecting plants.

3. If, however, such a process contains within the steps of sexually crossing and selecting an additional step of a technical nature, which step by itself introduces a trait into the genome or modifies a trait in the genome of the plant produced, so that the introduction or modification of that trait is not the result of the mixing of the genes of the plants chosen for sexual crossing, then the process is not excluded from patentability under Article 53 lit b EPC.

4. In the context of examining whether such a process is excluded from patentability as being “essentially biological” within the meaning of Article 53 lit b EPC, it is not relevant whether a step of a technical nature is a new or known measure, whether it is trivial or a fundamental alteration of a known process, whether it does or could occur in nature or whether the essence of the invention lies in it.”

Two aspects in the decision which are not related to the substantive questions of patentability are worthwhile mentioning:

In case G 1/08, only the opposition ground of exclusion from patentability was examined in the proceedings before the Opposition Division and the Board of Appeal. This did not exclude the possibility that patentability was lacking for other reasons, e.g. because of lack of novelty or inventive step. This raises the question whether a decision of the Enlarged Board of Appeal was required within the meaning of Article 112 (1) lit a EPC. The EBA answered the question in the affirmative and considered the referral to be admissible. Possibly, this conclusion was influenced by the fact that the points of law in cases G 2/07 and G 1/08 were closely related. If it is not clear whether a referred question is relevant to the final decision in the case giving rise to the referral, it is a question of procedural economy whether to deal first with the important point of law or the remaining questions (G 3/98, OJ EPO 2001, 62 – 6 month-period/UNIVERSITY PATENTS, Reasons pt. 1.2.4).

In T 83/05, Technical Board of Appeal raised the issue of whether the competence of the Administrative Council to amend the Implementing Regulations extends to core issues of substantive patent law. The EBA states that it is the function of the Implementing Regulations to determine in detail how the Articles should be applied and this does not exclude issues of substantive patent law. The only limit is seen in Article 164 (2) EPC according to which, in case of conflict, the provisions of the Convention shall prevail.

Reported by Dr. Rudolf Teschemacher

As to the problem of added subject-matter, EPO practice exhibits a specific feature which quite often turns out to be fatal to the patent in opposition proceedings. If the EPO considers a limiting amendment, made and allowed in grant proceedings, to have added new matter, the patentee falls into the inescapable trap resulting from the Enlarged Board’s of Appeal interpretation of the interaction of Article 123 (2) and (3) EPC in decision G 1/93: The amendment cannot remain in the claim because of the prohibition of adding new matter and it cannot be removed from the claim because of the prohibition of extending the scope of protection after grant. Board of Appeal 3.2.04 has increased this danger by applying this principle in the case of an unclear amended feature.

In the reported decision (not published in the Official Journal), the Board of Appeal interpreted a feature in the claim in two different ways, choosing, to the disadvantage of the patent proprietor, one of the possible interpretations as the basis for revocation as a limiting amendment which cannot be removed after grant in opposition proceedings before the EPO. The Board concluded that both interpretations represented common usage and held the amendment a limiting extension within the meaning of G 1/93. Thus, the patent was to be revoked.

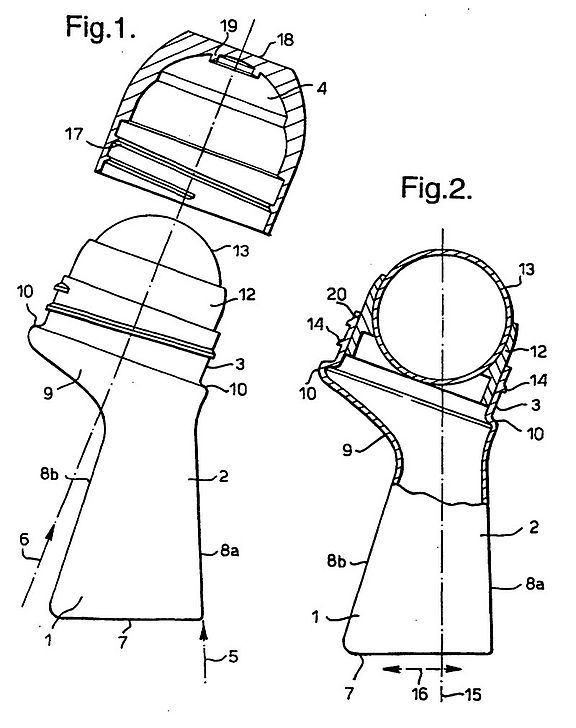

The invention concerns a roll-on applicator as known for cosmetic compositions like antiperspirants. The applicator comprises a container and head sections. The body of the container exhibits a shoulder. The anvil shape locates the hand of the user and increases stability. According to the granted claim the shoulder is formed by the front and rear walls, extending upwardly from the base which converge and thereafter diverge outwardly beyond the base footprint.

The term “base footprint” was introduced in grant proceedings replacing the previous term “base”. In the absence of a definition of the term “base footprint” in the application as originally filed, the patentee argued that “base footprint” means the same as “base”, i.e. the planar surface formed at the bottom of the container.

The Board of Appeal took the position that the term “base footprint” can be interpreted in two different ways, either as being limited to the planar surface or as including the rounded edge. In its second interpretation the Board considered the term as adding subject-matter beyond the application as filed. In the opinion of the Board, it did not matter that the claim could also be read in such a way that it did not add any subject-matter. However, the fact that in one reasonable interpretation of the claim it did add subject-matter was considered decisive. Thus, the Board concluded that the patent as granted could not be maintained.

The proprietor attempted to overcome the ground of opposition of added subject-matter by restoring the original terminology and requested to replace “base footprint” by “base”. Examining the scope of protection of both claim versions, the Board states that the claim as granted only protects embodiments with shoulders that extend further outward, whereas shoulders located between the planar contact surface boundary and that of the whole base (including the shoulder) projection did not fall within the scope of the granted claim. Thus, the reintroduction of the term “base” would result in removing a limitation of the claim. Here, again the fact that there is at least one reasonable, contextually consistent reading of the term that results in a limitation of scope, among a number of possible readings that do not, is considered decisive. The Board notes that if it were to construe an ambiguous undisclosed term in a manner favourable to the proprietor (i.e. in a way that does not add any subject-matter and limits the scope) it would act against the principle of a fair balance of interests underlying Articles 123 (2) and (3) EPC.

Remarks

The decision gives rise to two comments. First, national practice has shown that the interests of the public and the interests of the patentee can be safeguarded without facing the patentee with an inescapable trap. In its recent decision “Winkelmesseinrichtung” (GRUR 2011, 40) the German Federal Supreme Court, explicitly discussing the differing EPO approach, concludes that a limiting feature may remain in the claim. Of course, the added feature which was not originally disclosed may not be used as a basis for arguing inventive step

Second, it is the task of the Courts to interpret a patent for the purposes of assessing validity and infringement. The patent is a legal title. Any unclarities have to be removed when interpreting this title. The conclusion in T 567/08 that two interpretations are possible without concluding which one is the correct one is not such a decision. Rather, it is the denial to take a decision. Also in this respect a reference may be made to a recent judgment of the German Federal Supreme Court. In “Straßenbaumaschine” (GRUR 2009, 653), the Court states that the assessment of the claimed subject-matter is a question of law and concludes that, notwithstanding any unclarities, the judge cannot abstain from defining what the subject of the invention is.

Trademark Law

Reported by Dr. Alexander von Mühlendahl, J.D., LL.M.

“Bayerisches Bier” is an indication of geographical origin, well-known in Germany and elsewhere. The indication is protected under the European Union’s sui generis system of protection for designations of origin (aka “appellations of origin”) and geographical indications, both referred to in short as “GIs”. The request for protection was filed in September 1993, but the name was registered as a protected geographical indication only in 2001.

In the meantime, i.e. between the application and registration dates of BAYERISCHES BIER, the Dutch company Bavaria NV, which had been using BAVARIA since the late 1920s (but not in Germany), had obtained a trademark registration in Germany for a mark containing BAVARIA (the English equivalent of “Bayern”).

When the Bayerische Brauerbund sought to cancel the registration, based on the conflict rule between GIs and trademarks in Article 14 of Council Regulation (EC) No 2081/92 of 14 July 1992 on the protection of geographical indications and designations of origin for agricultural products and foodstuffs (in the meantime replaced by Council Regulation (EC) No 510/2006), they were successful in first and second instance, but the German Supreme Court referred a series of questions to the ECJ for a preliminary ruling interpreting these conflict rules. The specific question of interest in the present context was whether the conflict rules in Article 14 of Regulation No 2081/92 applied at all and from which point in time.

The ECJ ruled that the registration of a trademark which is identical or similar to a protected GI must be refused if the trademark was filed after the publication of the registration of the GI. Thus, as the protection for the BAVARIA mark was obtained prior to the registration of BAYERISCHES BIER, the cancellation cannot be obtained pursuant to Article 14 (1) of the Regulation.

Remarks

The outcome is surprising, because it departs from long-established principles in IP protection, namely the priority principle: first in time = first in right, and generally the filing date determines the priority, not the date of publication of registration. The successor legislation, Regulation (EC) No 510/2006, has a different conflict rule (the relevant point in time is the submission of the application to the Commission), which means that a case like the present one will not arise in the future.

Will BAVARIA prevail with its registration? This appears highly doubtful, in view of Article 14 (2) of Regulation 2081/92, according to which the registration of a mark can still be challenged if it was not validly registered under the law applicable to trademarks in general. Bayerischer Brauerbund has earlier German registrations of BAYERISCHES BIER as collective marks, and BAYERISCHES BIER was previously protected in Germany as a GI under German law.

Reported by Pascal Böhner

The German Federal Supreme Court decided that the licensor of a trademark license agreement can be obliged to pay compensation to its licensees after termination of the license agreement if licensor benefits from the customers acquired by the licensee.

The owner of the famous trademark “JOOP!”, a holding company not producing or marketing products itself, granted a license under this trademark according to which the licensee was entitled to manufacture, distribute and market men’s socks displaying the trademark “JOOP!”. When the owner of the mark claimed payment of outstanding license fees, the licensee set off payments against his claim for compensation for the established clientele of which the licensor may profit after termination of the license agreement.

The licensee claimed compensation according to a concept statutorily established for commercial agents. A commercial agent can claim compensation under Section 89 lit b of the German Commercial Code. The rationale of this statutory provision is that the principal/licensor benefits from the agent’s activities during the term of the agreement and after its termination, because the agent has acquired clients who then become clients of the principal/licensor. Such benefits, to some extent, have to be compensated to the agent.

This concept has been applied analogously to other forms of distribution systems, such as authorised dealers (mainly in the car distribution sector) and franchise agreements, under the following two conditions: (1) the licensee is integrated in the distribution system of the licensor and (2) the licensee is obliged to transfer the established clientele to licensor after termination of the agreement so that licensor is able to serve these customers won by licensee and to benefit from licensee’s acquisition activities.

In its “JOOP!” decision, the Federal Supreme Court explicitly found that this concept applies to trademark license agreements as well.

However, the Court held that the two conditions mentioned above were not met in the particular case, as the licensee was not integrated in the distribution system of the licensor. In fact, taking into account that the licensor had not distributed any products by itself, but only granted licenses under its trademarks, the Court found that there existed no licensor’s distribution system.

Remarks

The decision is of great importance for any owner of a trademark granting licenses for the use of his trademarks. The Federal Supreme Court clearly held that the concept of compensation claims for commercial agents can, under certain circumstances, apply to trademark license agreements and, as the case may be, substantial payments might be due.

In this regard, one has to be aware that the two above-mentioned conditions established by the case law may rather often be met in trademark license agreements, in particular where the licensee has to comply with the licensor’s requirements as regards marketing of products under the trademark. For example, where the license agreement imposes certain obligations on the licensee as regards “corporate identity”, quality and service requirements or joint advertising, the licensee is integrated in the licensor’s distribution system. As soon as the licensee is obliged to report names and addresses of its customers (which is often provided in the agreements in the context of sales reporting for calculating the license fees), the second condition will also be met (transfer of established clientele and ability to serve these customers, after termination of the agreement).

Further, it must be taken into account that, where the two conditions are met, compensation claims are mandatory and cannot be excluded in the license agreement. Therefore, licensors have to decide to what extent their licensees need to be integrated in the distribution system, as a high degree of integration can lead to substantial compensation claims. When building up a licensing strategy, these issues have to be considered with great attention.

Reported by Philipe Kutschke

The claimant challenged distribution of a chocolate Easter bunny of a competitor, allegedly infringing its three-dimensional Community trademark registration, comprising the shape of a sitting bunny in gold foil, ornamental drawings, a pleated red collar with a ribbon and golden bell, and comprising a logo consisting of figurative elements and the word elements “Lindt GOLDHASE” (“Lindt [a short form of the company name of the claimant] golden bunny”) on the bunny’s limb. The Easter bunny of the competitor, also comprised the shape of a sitting bunny in gold/bronze foil, ornamental paintings, a painted brown ribbon and a logo consisting of the word elements “RIEGELEIN CONFISERIE” (“Riegelein [a short form of the company name of the defendant] confectionary”) on the bunny’s limb. The case concerns distribution in Germany, however, the claimant is also challenging distribution of competitors’ chocolate bunnies in other countries.

The Frankfurt District Court dismissed the complaint. The Frankfurt Appeal Court confirmed the decision. Upon appeal of the claimant, the Federal Supreme Court overturned the decision in 2006 and remitted the case for further consideration to the Frankfurt Appeal Court, arguing that the Appeal Court had, inter alia, erred when assessing the distinctive character of the sign-in-suit (see IP Report 2006/VI).

After remand, the Frankfurt Appeal Court again rejected the complaint (see IP Report 2008/II). As regards the distinctive character of the sign-in-suit, the Court found that the results of the market surveys presented by the claimant demonstrated an increased degree of distinctiveness of the sign-in-suit, in particular arising from the designations “Lindt Goldhase” and the shape of the sitting bunny. Interestingly, the claimant had changed the motion for judgment at this stage of the proceedings insofar as they had replaced the pictures of the allegedly infringing Easter bunny by a product sample of the allegedly infringing Easter bunny in kind. The Court found that the product sample – contrary to the pictures of the alleged infringing bunny – revealed that the allegedly infringing bunny featured rather a bronze than a gold foil colour. Given that the Court found that there existed significant differences between the other distinctive elements of the conflicting signs (i.e. text elements, collar with ribbon, ornamental drawings), it came to the conclusion that the overall impression of the conflicting bunnies was dissimilar.

The claimant, obviously not satisfied by the decision, filed a further appeal with the Federal Supreme Court and succeeded. Surprisingly, the product sample of the allegedly infringing Easter bunny had disappeared. Consequently, the Federal Supreme Court was not in a position to review the Appeal Court’s findings and had to remit the case to the Appeal Court. Further, the Federal Supreme Court found that the Appeal Court had erred in its conclusions concerning assessment of the overall impression of the sign-in-suit arising from its distinctive elements, because it had not correctly analysed the relation of the individual distinctive elements to one another: The fact that the element of a trademark is per se distinctive does not necessarily mean that this element has a significant impact on the overall impression of the trademark. Furthermore, the Court criticized that the Appeal Court had not assessed whether the shape of the allegedly infringing bunny was perceived by the relevant public as a trademark.

Taking into account that the Appeal Court had found the colour of the conflicting bunnies to be dissimilar, and given that it had failed to assess the degree of similarity of the shapes of the conflicting signs, it was not admissible to transfer the perception of the public concerning the shape of the sign-in-suit (i.e., that the shape of the sign-in-suit was perceived as a sign demonstrating that these products originate from the same or from linked undertakings), to the allegedly infringing bunny. Finally, the Court had failed to correctly assess the overall impression of the allegedly infringing bunny. Consequently, the arguments of the Court were not qualified to demonstrate that the conflicting signs are dissimilar.

Remarks

It seems rather unlikely that the Appeal Court will change its mind as regards the dissimilarity of the conflicting signs, although it will have to significantly amend its reasoning. Thus, one can expect that both bunnies will continue to sit side-by-side in stores, cheering the heart of children at Easter time. Sweet as the bunnies may be, this is just another episode in a fierce battle of competitors offering similar products that are sold only over a short period of time in the year.

Design and Copyright Law

Reported by Dr. Alexander von Mühlendahl, J.D., LL.M.

Flos SpA brought an action for copyright infringement in Italy, claiming that a lamp called “Fluida”, imported from China and marketed in Italy, was a copy of the well-known “Arco” lamp (pictured hereafter) designed in 1962. The Milano court hearing the case on the merits was faced with copyright and design legislation raising doubts as to its compatibility with European Union law.

Under Italian law applicable prior to April 2001, when Italy implemented Directive 98/71/EC of 13 October 1998 on the legal protection of designs (Designs Directive), the “Arco” lamp was not eligible for copyright protection and had entered into the public domain. Article 17 of the Designs Directive provides for cumulation of copyright and design protection, leaving Member States free to determine the conditions under which copyright protection is available. Italy therefore amended its copyright law, allowing for the protection of designs meeting the requirements of copyright protection in general. However, as regards designs already in the public domain, Italian copyright law originally provided for a transition rule: for ten years after April 2001 rights would not be enforceable against those having before that time engaged in the manufacture, supply or marketing of products based on designs that had become part of the public domain. In 2007, Italian copyright law was amended again, and this time copyright protection for design having entered the public domain before April 2001 was totally excluded.

The questions presented to the ECJ for a preliminary ruling were the following:

“1. Must Articles 17 and 19 of Directive 98/71] be interpreted as meaning that, in implementing a (…) law of a Member State which has introduced copyright protection for designs into its legal order in accordance with that Directive, the discretion accorded to such a Member State to establish independently the extent to which, and the conditions under which, such protection is conferred may include discretion to preclude such protection in the case of designs which – albeit meeting the requirements for protection laid down in copyright law – fell to be regarded as having entered the public domain before the date on which the statutory provisions introducing copyright protection for designs into the domestic legal order entered into force, in so far as they had never been registered as designs or in so far as the relevant registration had already expired by that date?

2. If the answer to the first question is in the negative, must Articles 17 and 19 of Directive [98/71] be interpreted as meaning that, in implementing a national law of a Member State which has introduced copyright protection for designs into its legal order in accordance with that Directive, the discretion accorded to such a Member State to establish independently the extent to which, and the conditions under which, such protection is conferred may include discretion to preclude such protection in the case of designs which – albeit meeting the requirements for protection laid down in copyright law – fell to be regarded as having entered the public domain before the date on which the statutory provisions introducing copyright protection for designs into the domestic legal order entered into force and where a third party – without authorisation from the holder of the copyright on such designs – has already produced and marketed products based on such designs in that State?

3. If the answers to the first and second questions are in the negative, must Articles 17 and 19 of Directive [98/71] be interpreted as meaning that, in implementing a national law of a Member State which has introduced copyright protection for designs into its legal order in accordance with that Directive, the discretion accorded to such a Member State to establish independently the extent to which, and the conditions under which, such protection is conferred may include discretion to preclude such protection in the case of designs which – albeit meeting the requirements for protection laid down in copyright law – fell to be regarded as having entered the public domain before the date on which the statutory provisions introducing copyright protection for designs into the domestic legal order entered into force and where a third party – without authorisation from the holder of the copyright on such designs – has already produced and marketed products based on such designs in that State, where protection is precluded for a substantial period (a period of 10 years)?”

The questions were formulated with regard to Article 17 of the Designs Directive, which requires for its application that the subject matter is (or was) protected by a design right. It appeared in the course of the proceedings that the “Arco” lamp had never been protected in Italy by a design right. The ECJ concluded (Section 33 of the judgment) “that designs which, before the date of entry into force of the national legislation transposing [the Designs Directive] into the legal order of a Member State, were in the public domain because they had not been registered do not fall within the scope of Article 17 of the Directive.” The Court added that it is for the national court to determine whether copyright protection for such works could arise under other directives concerning copyright.

As regards the situation were a design right did exist, the ECJ concludes that it follows from Article 17 of the Designs Directive that a Member State may not totally exclude designs having entered into the public domain from copyright protection, answering the first question as follows:

“1. Article 17 of Directive 98/71/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 October 1998 on the legal protection of designs must be interpreted as precluding legislation of a Member State which excludes from copyright protection in that Member State designs which were protected by a design right registered in or in respect of a Member State and which entered the public domain before the date of entry into force of that legislation, although they meet all the requirements to be eligible for copyright protection.”

As regards the enforceability of copyright protection against products made on the basis of designs that had entered the public domain after no longer being protected as designs, the ECJ concludes that a transition period of 10 years, as in the original Italian legislation, or a complete exclusion from enforceability constitute infringements of Article 17 of the Designs Directive because they go beyond what is necessary or appropriate to protect legitimate interests of third parties:

2. Article 17 of Directive 98/71/EC must be interpreted as precluding legislation of a Member State which – either for a substantial period of 10 years or completely – excludes from copyright protection designs which, although they meet all the requirements to be eligible for copyright protection, entered the public domain before the date of entry into force of that legislation, that being the case with regard to any third party who has manufactured or marketed products based on such designs in that State – irrespective of the date on which those acts were performed.

Remarks

As the “Arco” lamp was never the subject of design protection in Italy, whether or not Flos will finally win will not depend on Article 17 of the Designs Directive, but on Italian copyright law directly. Italian copyright law has been amended in the meantime (2009) once more, this time providing for a right to use products made according to a design which had become part of the public domain prior to April 2001, but apparently only with regard to products made before that date.