IP Report 2012/IV

Patent Law

Reported by Professor Dr. Alexander von Mühlendahl, J.D., LL.M

On July 12, 2012, the Court of Justice of the European Union (ECJ) handed down its long-awaited decision in the “Solvay” matter, related to whether courts in the EU having jurisdiction over an alleged infringer have the competence to adopt trans-border or “pan-European” preliminary measures including preliminary injunctions. The ECJ cleared the path for trans-border preliminary measures.

Solvay brought infringement proceedings in The Netherlands against a number of Honeywell companies for infringement of European patents valid in a number of Member States, seeking preliminary relief under Dutch procedural law. Solvay invoked the jurisdiction of the Dutch courts as the courts in the Member State of the domicile of one of the defendants, pursuant to Article 2 of Council Regulation (EC) No 44/2001 on jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters, the so-called Brussels-I-Regulation, successor to the 1968 Brussels Convention, as well as on Article 6 No 1 Brussels-I-Regulation which allows the joinder of several parties before the courts of the Member State where one of them is domiciled “when the claims are so closely connected that it is expedient to hear and determine them together to avoid the risk of irreconcilable judgments resulting from separate proceedings.” As the case presented issues of prosecuting patent infringement in several Member States, and as previous ECJ decisions had seemed (almost) to close the door to such actions, the District Court (Rechtbank) in The Hague referred the following question to the ECJ:

Regarding Article 6 (1) of Regulation No 44/2001:

1. In a situation where two or more companies from different Member States, in proceedings pending before a court of one of those Member States, are each separately accused of committing an infringement of the same national part of a European patent which is in force in yet another Member State by virtue of their performance of reserved actions with regard to the same product, does the possibility arise of “irreconcilable judgments” resulting from separate proceedings as referred to in Article 6 (1) of Regulation No 44/2001?

Regarding Article 22 (4) of Regulation No 44/2001:

2. Is Article 22 (4) of Regulation No 44/2001 applicable in proceedings seeking provisional relief on the basis of a foreign patent (such as a provisional cross-border prohibition against infringement), if the defendant argues by way of defence that the patent invoked is invalid, taking into account that the court in that case does not make a final decision on the validity of the patent invoked but makes an assessment as to how the court having jurisdiction under Article 22 (4) of (that) Regulation would rule in that regard, and that the application for interim relief in the form of a prohibition against infringement shall be refused if, in the opinion of the court, a reasonable, non-negligible possibility exists that the patent invoked would be declared invalid by the competent court?

3. In order for Article 22 (4) of Regulation No 44/2001 to be applicable in proceedings such as those referred to in the preceding question, must the defence of invalidity be subject to procedural requirements in the sense that Article 22 (4) of the Regulation is only applicable if invalidity proceedings before the court having jurisdiction under Article 22 (4) of (that) Regulation are already pending or are to be commenced within a period to be laid down by the court or at least that a summons in that regard has been or is being issued to the patent holder, or does it suffice if a defence of invalidity is merely raised and, if so, are requirements then laid down in respect of the content of the defence put forward, in the sense that it must be sufficiently substantiated and/or that the conduct of the defence must not be deemed to be an abuse of procedural law?

4. If question (2) is answered in the affirmative, does the court, after a defence of invalidity has been raised in proceedings such as those referred to in question 1, retain jurisdiction in respect of the infringement action with the result that (if the claimant so desires) the infringement proceedings must be stayed until the court having jurisdiction under Article 22 (4) of Regulation No 44/2001 has given a decision on the validity of the national part of the patent invoked, or that the claim must be refused because a defence that is essential to the decision may not be adjudicated, or does the court also lose its jurisdiction in respect of the infringement claim once a defence of invalidity has been raised?

5. If question (2) is answered in the affirmative, can Article 31 of Regulation No 44/2001 confer on the national court jurisdiction to adjudicate on a claim seeking provisional relief on the basis of a foreign patent (such as a cross-border prohibition against infringement), and against which it is argued by way of defence that the patent invoked is invalid, or (should it be decided that the applicability of Article 22 (4) of (that) Regulation does not affect the jurisdiction of the Rechtbank [s’-Gravenhage] to adjudicate on the infringement question) jurisdiction to adjudicate on a defence claiming that the foreign patent invoked is invalid?

6. If question (5) is answered in the affirmative, what facts or circumstances are then required in order to be able to accept that there is a real connecting link, as referred to in paragraph 40 of the judgment (in Case C-391/95 Van Uden [1998] ECR I-7091), between the subject matter of the measures sought and the territorial jurisdiction of the Contracting State of the court before which those measures are sought?

In its judgment of July 12, 2012, the ECJ ruled as follows:

1. Article 6 (1) of Council Regulation (EC) No 44/2001 of December 22, 2000 on jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters, must be interpreted as meaning that a situation where two or more companies established in different Member States, in proceedings pending before a court of one of those Member States, are each separately accused of committing an infringement of the same national part of a European patent which is in force in yet another Member State by virtue of their performance of reserved actions with regard to the same product, is capable of leading to ‘irreconcilable judgments’ resulting from separate proceedings as referred to in that provision. It is for the referring court to assess whether such a risk exists, taking into account all the relevant information in the file.

2. Article 22 (4) of Regulation No 44/2001 must be interpreted as not precluding, in circumstances such as those at issue in the main proceedings, the application of Article 31 of that regulation.

Remarks

I. Introduction

In the European Union patents are granted as European patents by the European Patent Office or by national patent offices in the 27 Member States. In both cases, the patents are national patents subject to national law, especially as regards infringement and sanctions. This presents problems for patent proprietors when seeking to enforce their patents and the infringement has been committed or threatened in more than one Member State (“trans-border infringements”) and multiple potential defendants are involved, notably as regards the determination of which courts have international jurisdiction.

For the EU Member States the applicable rules are found in the Brussels-I-Regulation. For the Member States of the European Free Trade Agreement (EFTA), which includes all EU Member States and Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland, the rules are found in the Lugano Convention of October 30, 2007 on Jurisdiction and the Recognition and Enforcement of Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters (Lugano II), which is the successor agreement to the first Lugano Agreement adopted in Lugano on September 16, 1988. Under the Brussels-I-Regulation and under Lugano II, EU-wide (EFTA-wide) jurisdiction in cases of trans-border infringements is established as regards defendants domiciled in the EU or the EFTA at the courts of the Member State where the defendant is domiciled (Article 2 [1] Brussels-I-Regulation, Article 2 [1] Lugano II), or alternatively in the Member State where acts of infringement have been committed or threatened (Article 5 No 3 Brussels-I-Regulation, Article 5 No 3 Lugano II). Furthermore, Article 6 No 1 Brussels-I-Regulation (Article 6 No 1 Lugano II) allows the joinder of several parties before the courts of the Member State where one of them is domiciled “when the claims are so closely connected that it is expedient to hear and determine them together to avoid the risk of irreconcilable judgments resulting from separate proceedings.”

Applying these rules to trans-border patent infringements brings complicated problems with it because of the territorial nature of patent rights and the provision in Article 22 No 4 Brussels-I-Regulation (Article 24 No 4 Lugano II) which provides for exclusive jurisdiction of the courts of the Member State having granted the patent or in which the patent, in the case of European patents), is valid when the issue is the validity of that patent.

II. GAT/LuK and Roche Nederland

In two judgments of July 13, 2006, the ECJ interpreted these provisions in a way making enforcement of trans-border patent infringement of European patents very difficult if not impossible.

In Case C-4/03, Gesellschaft für Antriebstechnik mbH & Co. KG v. Lamellen und Kupplungsbau Beteiligungs KG, commonly called „GAT/LuK“, the question presented by the Dusseldorf Court of Appeal was how the predecessor to Article 22 No 4 Brussels-I-Regulation was to be interpreted when the defendant in that case, accused of infringing a European patent valid in France, raised the defense of invalidity of that patent. The ECJ held that raising the defense of invalidity was no different from seeking a declaration of invalidity:

Article 16 (4) of the [Brussels] Convention of September 27,1968 (…) is to be interpreted as meaning that the rule of exclusive jurisdiction laid down therein concerns all proceedings relating to the registration or validity of a patent, irrespective of whether the issue is raised by way of an action or a plea in objection.

In Case C-539 /03, Roche Nederland BV v Primus, “Roche Nederland”, the question presented by the Dutch Supreme Court was whether the predecessor to Article 6 No 1 Brussels-I-Regulation could apply when several defendants belonging to the same group of companies were accused of infringing the same European patent in several Member States. The ECJ concluded as follows:

Article 6 (1) of the (Brussels) Convention (…) must be interpreted as meaning that it does not apply in European patent infringement proceedings involving a number of companies established in various Contracting States in respect of acts committed in one or more of those States even where those companies, which belong to the same group, may have acted in an identical or similar manner in accordance with a common policy elaborated by one of them.

The reason for this holding was that since these patents are subject to the law of the respective Member State the factual and legal situation would not be the same, and thus one of the requirements for applying that provision was not met.

III. Provisional conclusions

1. Defense of invalidity

GAT/LuK established that a court having international jurisdiction is not competent to decide on the validity of an allegedly infringed patent valid in another Member State, regardless of whether the patent is attacked directly or indirectly. While this was broadly criticised because the “defense” did not constitute the “subject matter” (“Gegenstand”) of the case, and the “concerning” in the English version of Brussels-I-Regulation or the Brussels Convention was not an accurate rendering of the language in the other versions, a return to a different reading is practically excluded, and now even more so than before, since Lugano II expressly incorporates that interpretation in its Article 22 No 4, which reads as follows (emphasis added):

“(…) in proceedings concerned with the registration or validity of patents, trademarks, designs, or other similar rights required to be deposited or registered, irrespective of whether the issue is raised by way of an action or as a defence, the courts of the State bound by this Convention in which the deposit or registration has been applied for, has taken place or is, under the terms of a Community instrument or an international convention, deemed to have taken place. Without prejudice to the jurisdiction of the European Patent Office under the Convention on the grant of European patents, signed at Munich on October 5 1973, the courts of each State bound by this Convention shall have exclusive jurisdiction, regardless of domicile, in proceedings concerned with the registration or validity of any European patent granted for that State irrespective of whether the issue is raised by way of an action or as a defence.”

GAT/LuK more or less ended the practice of courts notably in Germany and in The Netherlands of accepting jurisdiction in trans-border infringement cases. Whether this was (and is) actually justified depends very much on the consequence of a defense of patent invalidity. The one (extreme) position would be that the court seized loses its jurisdiction also as regards the infringement claim. The other (moderate) position would be that the argument of invalidity is inadmissible and the court would be entitled (indeed obliged) to continue the infringement action, with the possibility of suspending that action when the invalidity is properly made an issue in the Member State where the patent is valid.

Question 4 referred in the Solvay case raised that very issue. However, the ECJ did not reach that question as the condition of an affirmative answer to Question 2 was not met (see Paragraph 52 of the Solvay decision).

We would strongly argue in favor of the moderate interpretation, which in our view is the only one compatible with the fact that the court properly seized with the infringement claim cannot be ousted of that jurisdiction as the result of a defense which, on its merits, must be adjudicated in another Member State.

2. Multiple defendants

As regards the interpretation of Article 6 No 1 (joinder of defendants) the judgment of the ECJ is solid: different patents, even though European, are different as to law and facts – thus, no joinder possible. Interestingly, the same ECJ, a few years later, allowed a joinder of parties not related among each other for the same act of (alleged) copyright infringement committed in various Member States even though the actual degree of harmony in the field of patents is quite advanced, at least as much as in the field of copyrights, although admittedly a harmonization directive applied (decision of December 1, 2011, Case C-145/10, Painer).

IV. Solvay

Solvay has moved the clouds hanging over trans-border litigation somewhat.

1. Multiple defendants

Roche Nederland was a case where each of the different defendants was accused of infringing the same European patent in different Member States. In contrast, in Solvay the situation was such that all of the defendants were accused of infringing the same European Patent in the same Member State. In that situation the ECJ was willing to accept that the possibility of “irreconcilable judgments” exists. Thus, provided the facts are the same or sufficiently similar, it is indeed possible for multiple parties to be joined before a court which is not in the Member State where the patent is allegedly infringed.

2. Preliminary actions

GAT/LuK was a case where the defense of invalidity of the French patent before the Dusseldorf court was raised in the main action. In contrast, in Solvay the case was one for preliminary relief. The ECJ analysed in detail the purpose and scope of the jurisdiction in preliminary proceedings (Article 31 Brussels-I-Regulation) and the reasons for the earlier GAT/LuK judgment, holding that in cases where the court would not judge even implicitly the validity of the allegedly infringed patent, preliminary relief could be granted even with regard to Member States other than the forum state.

V. Consequences

After Solvay, all courts in the EU (and in EFTA countries) having jurisdiction over an alleged infringer have the competence to adopt trans-border or “pan-European” preliminary measures including preliminary injunctions.

Consequently, German courts may, by preliminary injunction, order cessation of infringement of patents in all EU (or EFTA) Member States where acts of infringement are committed or threatened.

Similarly, German courts may order any other preliminary relief available, such as seizure of infringing products, or the disclosure of information regarding the origin or destination of infringing products.

The clearer the case of infringement, the more likely it is that a German court will issue such preliminary measures with effect in all countries where the claimant enjoys patent protection.

In preliminary relief cases before German courts, the defense of the (alleged) invalidity of the asserted foreign patent is not admitted, just as the defense of invalidity of an asserted German patent is not allowed.

Reported by Dr. Thomas Gniadek

A plaintiff is not barred from bringing an action not restricted to a certain attacked embodiment, but may assert a subject-matter which shall cover further embodiments falling under the scope of the patent-in-suit. The plaintiff may phrase its request for an injunction according to the wording of the respective claim of the patent-in-suit without including a reference to the specific attacked embodiment submitted with its complaint. As a rule, such broad phrasing of the request does not result in the subject-matter of the complaint comprising (all) further embodiments falling under the scope of the patent-in-suit. Instead, the subject-matter is defined by the phrasing of the request and the submitted facts and, thus, comprises all embodiments having (essentially) the same technical design – with respect to the features of the patent-in-suit – as the attacked embodiment submitted with the complaint.

In the present case, the plaintiff attacked the defendant for infringement of claim 1 of the German Patent DE 195 16 780 C1 (in the following “patent-in-suit”) concerning a hydrodynamic nozzle for the cleaning of pipes and ducts. The plaintiff succeeded in first instance proceedings. However, in the appeal proceedings, the defendant referred to an earlier, final “judgment by default” having dismissed the action and which also concerned the patent-in-suit and a pipe cleaning nozzle distributed by the defendant. Therefore, the Appeal Court set aside the first instance judgment in the case at hand and dismissed the action as inadmissible.

The Appeal Court held that there was a conflicting legal effect of the earlier judgment by default (res judicata pursuant to Section 322, German Code of Civil Procedure) as the requirements for conflicting res judicata were met. First, the earlier judgment concerned the same parties of the proceedings, the plaintiff in the proceedings at hand being a legal successor of the plaintiff in the earlier proceedings, and the defendant of both proceedings being the same. Second, the Appeal Court found that the subject-matter of the two proceedings was the same, since (a) in both proceedings the request for an injunction was phrased identically – namely stating the wording of claim 1 of the patent-in-suit without citing any specific attacked embodiment – and since (b) the facts submitted for reasoning the complaint with respect to the attacked embodiment were identical.

The respective plaintiffs of both proceedings had submitted a tangential fitting of the outer line of the outer diameter of the duct at the first radius of the basis of the distribution chamber. Against this background, the Appeal Court was of the opinion that the new factual submission of the plaintiff with respect to the existence of an “edge” near the openings of a press water outlet of the attacked embodiment in the earlier proceedings – whereas the attacked embodiments in the proceedings at hand showed a seamless junction – was irrelevant. Only the past submission in the earlier proceedings was decisive for determining the scope of the subject-matter of the earlier judgment by default. In the earlier proceedings, no “edge” had been submitted or used to argue infringement.

The Federal Supreme Court held that the subject-matter of the earlier proceedings and the proceedings at hand was different and that, therefore, there was no res judicata. Thus, the Federal Supreme Court set the Appeal Court’s decision aside and remitted the matter to the Appeal Court.

In its reasoning, the Federal Supreme Court outlined that the subject-matter of patent infringement proceedings is to be determined according to the phrasing of the request for an injunction and the facts submitted in view of the allegedly infringing embodiments. Regarding the latter, the elements of the submitted attacked embodiments are decisive which are explained to argue infringement. Thus, the subject-matter of patent infringement proceedings is essentially determined by the very technical design of the attacked embodiment submitted with the complaint in view of the features of the respective claim of the patent-in-suit. An identity of the subject-matter cannot be assumed if the core of these facts is changed by new facts.

According to the Federal Supreme Court, the plaintiffs in the two proceedings based their action on different facts in view of the features of the respective claim of the patent-in-suit. The realization of the decisive feature of the respective claim was argued on the basis of different technical designs of the pipe cleaning nozzle. The existence of an “edge” at the embodiments attacked in the earlier proceedings followed from an illustration of these embodiments which the plaintiff of the earlier proceedings referred to when arguing its case.

Moreover, the Federal Supreme Court explained that the finding of a different subject-matter in the earlier proceedings as opposed to the proceedings at hand is not excluded by the fact that both plaintiffs relied on identically phrased applications for an injunction – namely just stating the wording of claim 1 of the patent-in-suit without referring to a specific attacked embodiment. A plaintiff is not barred from bringing an action not restricted to a certain attacked embodiment, but may assert a subject-matter which shall cover further embodiments falling under the scope of the patent-in-suit. However, generally, such broad action does not simply follow from a request for an injunction not expressly limited to a certain specific embodiment. Instead, the request for an injunction must be interpreted under consideration of the plaintiff’s factual submission in line with the legal rules outlined above. It is not the wording of the application but the plaintiff’s material demand which defines the subject-matter of patent infringement proceedings.

Remarks

The present decision is important as to the definition of the subject-matter in patent infringement proceedings having numerous implications to related legal issues. Contrary to the previous Federal Supreme Court’s decision “Blasfolienherstellung” (cf. GRUR 2005, 569), the Federal Supreme Court held that it is advisable, but not necessary, to refer to a specific attacked embodiment in the wording of a request for an injunction. In this regard, the Federal Supreme Court follows the established practice of the Dusseldorf Appeal Court. By stating that the subject-matter comprises all embodiments having (essentially) the same technical design – with respect to the features of the patent-in-suit – as the attacked embodiment submitted with the complaint, the Federal Supreme Court clarifies that the embodiments affected by the proceedings are neither any further embodiments falling under the scope of the patent-in-suit nor any very specific embodiments listed in the complaint. In this regard, the Federal Supreme Court repeats the so-called “core theory” with respect to the scope of enforcement of a decision finding infringement.

Reported by Dr. Axel B. Berger

Possession of an invention is required at the filing date in order to claim a right based on prior use with respect to the protected invention. Such possession is deemed to exist if the technical teaching of the invention is objectively completed and if it is subjectively recognized that the actual implementation of the invention is possible. The latter is indicated if the action taken is methodically aimed at the realization of a technical teaching realizing all features of the subject-matter according to the invention.

In the case at hand, the plaintiff filed an infringement complaint with the District Court Dusseldorf based on a utility model against a manufacturer of a pharmaceutical who manufactures its product in Austria and markets it also in Germany. The utility model is directed to a composition comprising Desmopressin which is inter alia delimited by the feature that the level of oxidants is equal to or below 15 parts per million (ppm). In first instance proceedings, the defendant successfully referred to its right of prior use, since it marketed the composition as claimed only three months after the priority date of the utility model which required preparing measures before the priority date such as the application for a marketing authorisation in Germany or a distribution agreement with a sales partner.

During appeal proceedings, the plaintiff limited its claims in auxiliary requests to compositions having inter alia a level of oxidants of less than 5 ppm. The plaintiff argued that it had been known that the active substance Desmopressin is susceptible to rapid degradation leading to a reduced storage life of the pharmaceutical. With the finding that it is the presence of “carryover” oxidants which are responsible for the degradation of Desmopressin, the problem of overcoming limited storage life would have been solved by the provision of a pharmaceutical composition having a level of oxidants of 15 ppm or less. The plaintiff alleged that the defendant did not know about the correlation between the contained oxidant level and Desmopressin degradation/storage life time and, thus, disputed that the defendant was in possession of the invention. As a result, the appeal of the plaintiff was rejected.

The Federal Supreme Court now confirmed the appeal decision stating that the possession of an invention as required for a right based on prior use pursuant to Section 12 (1) German Patent Act is deemed to exist if the technical teaching of the invention is objectively completed and if it is subjectively recognized that the actual implementation of the invention is possible. This is the case if the technical teaching is applied repeatedly, i.e. if the technical teaching is methodically aimed at the realization of the technical teaching, as opposed to realizations during an experimental stage or if the realization is merely achieved “by chance” in only some instances.

However, it is not required that the acting person has knowledge of advantageous effects exceeding the finding of the asserted realizability of the invention, i.e. knowledge of any effects that are not reflected in the claims. Consequently, the Court finds that the defendant would have been in the possession of the invention, since the defendant already decided before the priority date of the utility model on the exact formulation of the pharmaceutical, which inevitably and reliably also leads to a level of oxidants according to the invention of 3.8 ppm (i.e. below 15 ppm or 5 ppm). A positive knowledge of the fact that the level of oxidants may not exceed 15 ppm or 5 ppm, due to the positive effect of such formulations with a low level of oxidants on the storage life of a composition comprising Desmopressin, was not required.

Remarks

With its decision the Federal Supreme Court defines one of the previously established requirements for assuming possession of an invention with respect to the right based on prior use – namely that the technical teaching must be subjectively recognized such that the actual implementation of the invention is possible. According to the Federal Supreme Court, this criterion requires (only) that the implementation of the technical teaching is indeed aimed at the methodical realization of said technical teaching. The same applies with respect to another well-established prerequisite – namely that the acting person knows about the relationship of cause and effect. A good indication for this is that the teaching is realized in a repeated manner.

Moreover, the decision at hand highlights the importance and scope of prior use rights, since in fact the complaint was not only directed against the manufacturer of the pharmaceutical but also to its sales partner in Germany. The Federal Supreme Court upheld the decision to reject the complaint also with respect to the sales partner. In this regard, the Court emphasized that the right based on prior use is of broad nature and is not limited in quantity. Thus, said right based on prior use extends to any subsequent distributor and allows establishing a sales network, with, if intended, several sales partners.

Reported by Michael Kobler

The established case law of the Federal Supreme Court on the distinction between repair and reconstruction in cases of indirect patent infringement applies to direct infringement as well. Regarding replacement of spare parts, it is decisive for finding infringement whether such parts are usually expected to be replaced during the life of the product, i.e. whether their replacement is regarded as a usual means of conservation and whether such replacement does not change the identity of the complete product as a marketable economic asset.

The plaintiff produces and distributes pallet containers in accordance with claim 1 of the patent-in-suit. Defendants offer to third parties refurbished pallet containers, which have initially been put on the market by the plaintiff, having removed the original inner containers of the pallet containers and replaced them with similar inner containers of their own production.

The Federal Supreme Court held that the decision of the Munich Appeal Court is legally defective and must be set aside, because the Munich Court of Appeals did not accurately apply the following legal principles:

The defendants’ act of refurbishing pallet containers may constitute patent infringement if, in this regard, the plaintiff’s patent right is not exhausted. According to the established case law, the patent holder’s exclusive right is exhausted regarding patented products that have been put on the market with his consent. Therefore, the purchaser of such products is entitled to use them and to sell or offer them for sale to third parties.

In the case at hand, the Federal Supreme Court outlined that not only a purchaser but also the defendants having refurbished the respective device may generally benefit from the doctrine of exhaustion, and might therefore use and resell the respective device, because such entitlement is not based on a contractual granting of rights by the patent holder and therefore restricted to the purchaser; rather, in case of exhaustion of rights, the patent holder is generally deprived of his right to exclude others from the use of the patented invention, with respect to this very product.

The use of a patented invention permitted under the doctrine of exhaustion includes maintenance and re-establishment of usability of the specific product if the function or performance of the specific product is impaired, or lost in whole or in parts by wear or damage, or on other grounds. However, if the measures taken do not maintain the identity of the product put on the market with the patent holder’s consent, but in fact amount to a “making again” of the patented product, such measures would exceed the defendants’ right to use and would thus constitute patent infringement.

Thus, in the case at hand, the decisive question is whether replacing the inner container amounts to making a new pallet container. In this respect, according to established case law regarding the replacement of spare parts, the issue of maintaining the identity of the refurbished device, or making a new device, can only be determined in the light of the subject matter of the invention and, by way of a balancing of the legitimate interest of the patent holder in a commercial exploitation of the invention, on the one hand, and the interests of the purchasers in an unrestricted use of the patented product put on the market, on the other hand.

The Federal Supreme Court outlined that primarily it must be assessed whether the replaced parts are usually expected to be replaced during the working life of the product according to the prevailing understanding of the public, meaning the legitimate expectations of the purchasers of such containers. If not, the replacement amounts to “making the product again” and, thus, to patent infringement, even if the replaced parts do not reflect the technical effects of the invention. If the respective parts are expected to be replaced, generally, the replacement does not amount to “making the products again”, it does not constitute patent infringement, unless the replaced parts do reflect the core of the invention. In the latter case, the patent is infringed, since the technical and economic advantage of the invention is realized again. In summary, the Federal Supreme Court emphasized that the understanding of the public is the first key aspect, and that technical aspects are only relevant as a corrective for finding infringement if, according to the understanding of the public, there was no patent infringement.

Remarks

With “Palettenbehälter II”, the Federal Supreme Court continues its case law on the distinction between repair and reconstruction established in the decision “Flügelradzähler” (GRUR 2004, 758; English translation in IIC 2005, 963) and further elaborated in “Laufkranz” (GRUR 2006, 837) and “Pipettensystem” (GRUR 2007, 769). Whereas these were all cases of indirect infringement, in which the respective patent holders attacked suppliers of spare parts, in the case at hand, the established principles are applied to direct infringement by a competitor.

The mere fact that, in the course of the last eight years, there have been as many as four judgments on the distinction between repair and reconstruction by the Federal Supreme Court shows the practical importance of this issue. Patent holders and purchasers of patented products are therefore well advised to include terms and conditions into their sales agreements as to purchasers’ right to repair and refurbish. This is so all the more, because the Federal Supreme Court’s ruling in “Palettenbehälter II” – in particular regarding the case-by-case balancing of interests and the difficulties of determining the prevailing understanding of the public – does not in every case provide for an adequate amount of legal certainty.

Reported by Dr. Rudolf Teschemacher

In the case underlying the referral of a point of law to the Enlarged Board of Appeal (EBA), the patent had been opposed on the grounds that a feature in claim 1 of the granted patent had not been disclosed in the application as filed. The proprietor of the patent argued that this resulted from a typographical error made when amending this claim during grant proceedings and that the word “position” in this feature should read “portion”.

On his request, the opposition division took the interlocutory decision to stay opposition proceedings and to remit the case to the examining division for a decision on the proprietor’s request for correction of the decision to grant under Rule 140 EPC. On the opponent’s appeal, the Board of Appeal considered that there was a fundamental point of law and referred the questions to the EBA whether a request for correction of the grant decision filed after the initiation of opposition proceedings is admissible and, if yes, whether the examining division’s decision is binding upon the opposition division.

The EBA answered the questions as follows:

1. Since Rule 140 EPC is not available to correct the text of a patent, a patent proprietor’s request for such a correction is inadmissible whenever made, including after the initiation of opposition proceedings.

2. In view of the answer to the first referred question, the second referred question requires no answer.

In the reasons for the decision, the EBA emphasizes the need for legal certainty and the protection of third parties and notes that the proprietor has adequate remedies available to ensure that the text of the granted patent is correct. Before grant, the text of the application intended for grant has to be communicated to the applicant for his final approval and an error like a misspelt or incorrect word can be corrected under Rule 139 EPC. If the decision to grant contains an error made by the examining division after the applicant’s final approval, so that the text of the patent as granted is not that approved by the proprietor, the proprietor is adversely affected and is entitled to appeal the grant decision.

In addition, the EBA notes that the granted patent is subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the Contracting States and concludes therefrom that there is no reason why any subsequent decision of the EPO (other than in opposition or limitation proceedings) to change the text of the granted patent should be recognized in those jurisdictions. Furthermore, the EBA considers that the absence of a possibility to request corrections of the text of the patent under Rule 140 EPC should not prejudice patent proprietors.

Remarks

Rule 140 EPC stipulates that linguistic errors, errors of transcription and obvious mistakes in decisions of the EPO may be corrected. A need to correct a final decision obviously can only arise after the conclusion of the proceedings before the deciding body, i.e. when this body has ceased to be competent in the matter. The competence for correction of the decision has to be seen as an annex to the previous competence, or a limited competence for the deciding body to bring the text of its decision into conformity with what was intended to be decided when the decision was given. This appears to be widely accepted in national and international procedural law and there is no reason why this should not apply to decisions of the EPO.

The question referred to the EBA addressed the problem of the relation between the competence of the examining division to correct its decision to grant and the competence of the opposition division to decide on the validity of the patent. Apparently, the referring Board took it as granted that a possibility to correct the decision to grant in respect of the text of the patent exists.

This assumption seemed to be justified for at least two reasons. First, whereas the EBA, referring to G 1/97 and to the history of the provision, observes that Rule 140 should be limited to its restricted wording, nothing in the wording of the provision or in its legal history indicates that the provision should not be applied to the most common and frequent decision of the EPO which is the decision to grant. Second, the previous decision G 8/95 (OJ EPO 1996, 481), not cited in the reported decision, has to be mentioned, in which the EBA was faced with the question whether a Technical Board of Appeal or the Legal Board of Appeal was competent to decide on an appeal against the refusal of a request to correct the decision to grant in respect of the text of the patent. The EBA decided that it was the task of the Technical Boards of Appeal “inter alia considering …such a request is based on the allegation that there is a linguistic error, error of transcription or similar obvious mistake. This opportunity for corrections is a principle known in many legal systems (see e.g. Article 66 of the Rules of Procedure of the European Court of Justice); where a decision does not express the manifest intention of the deciding body, an obvious clerical mistake in the decision can be corrected.” This does not give the impression that such a request might be inadmissible from the outset, and indeed, before and after G 8/95, it was the consistent practice of the first instance and the Boards of Appeal that such requests were admissible. Thus, it is no surprise that neither the President of the EPO nor the two amici curiae in their comments on the referral even mentioned the possibility that Rule 140 EPC might not allow the correction of the text of the granted patent.

It is true that there was no uniform case law on the question how to deal with a request for correction of the decision to grant after opposition proceedings had been initiated, and it is also true, as pointed out by the President of the EPO, that applicants were tempted to use Rule 140 EPC beyond its proper limits. The EBA solved all problems by cutting the Gordian knot and declared Rule 140 EPC as not applicable at all to a request for correcting the decision to grant in respect of the text of the granted patent, i.e. also to a request before any opposition proceedings have been initiated, in particular to a request in reaction to the decision to grant. The EBA observes that this result “should not prejudice patent proprietors. If a correction would be obvious (as it should be to satisfy Rule 140 EPC), there can be no surprise and no adverse effect on opponents or others, because all concerned should read the patent as if corrected and an actual correction should not be necessary. If, on the other hand, a correction would be less than immediately obvious, then it should not in any event be allowed.” This consideration may be quite correct for the facts of the case underlying the referring decision.

However, there are quite different situations in which a correction of the decision to grant may be considered justified. Supposed the examining division, when assembling the documents intended for grant, mixes up the applicant’s requests or omits one of the pages, this mistake will be obvious from the content of the file, but it will not be obvious from the granted patent. Thus, only the deficient text of the patent specification will be the basis for the interpretation of the patent. The applicant, having overlooked the mistake when receiving the communication pursuant to Rule 71 (3) EPC, had so far did have the possibility to request a correction of the decision to grant – which the EBA has taken away. The possibility of filing an appeal remains, but it presupposes that the mistake is detected within the time limit for filing an appeal. Whereas the EBA correctly emphasizes that the applicant has to approve the text intended for grant and to check the documents of which he is informed under Rule 71 (3) EPC, sight should not be lost of the fact that the prosecution of patent applications is a routine business (in 2010: 62.112 published patents) in which occasional mistakes are unavoidable. If the EPO makes the mistake, this remains without detrimental consequences for the Office, if the applicant makes the mistake, the value of his title is endangered and if an attorney makes the mistake, his personal liability for an incalculable risk may be at stake.

Therefore, the users of the European patent system should consider the information of the intention to grant not only as a welcome success in the grant proceedings. Rather, they should keep in mind that a final and thorough check has still to be made in order to detect any errors which may have been made in the preceding proceedings in order to correct them before the decision to grant as far as still possible.

Design Law

Reported by Dr. Henning Hartwig

On March 8, 2012, the German Federal Supreme Court gave further guidance on how to deal with deviating representations of a Community design being asserted against a later device.

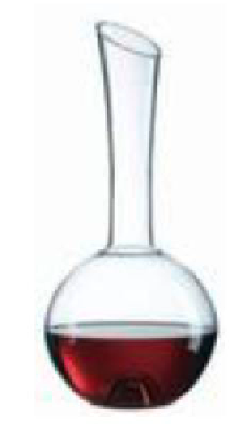

The claimant sought a judgment of infringement on the basis of its registered Community design which consisted of the following representations

against the following product

The Court, firstly, found that a distinction must be made between the subject matter of a registered design and its scope of protection. The subject matter must be taken from the various views of the appearance of the whole or a part of a product resulting from the application as filed. Different as well as inconsistent representations of a Community design do not establish different subject matters; rather, each design application constitutes one subject matter. However, inconsistencies in representing one subject matter require that the Court clarifies the exact identity of such subject matter. This must be done by way of interpretation, including the (mandatory) indication of the product or the (facultative) description of the design or the (facultative) classification of the product.

Where – as in the underlying case – the various views of the registered design were inconsistent, i.e., showing a base in one representation but not in another, it is appropriate to limit the specific subject matter to the greatest common subset, i.e., including those features that can be seen from all the different views.

Turning to the infringement test, i.e., whether the accused device produces the same overall impression on the informed user as the asserted Community design, the Supreme Court confirmed the findings of the lower instance finding non-infringement due to the fact that the asserted design is characterized also by its base which is missing in the accused design.

In this context, the Supreme Court held that the asserted design’s scope of protection cannot be reduced to the appearance of a wine decanter without a base, i.e., to limit the design as such to only a part of the representation. The reason is that a registered Community design disclosing the appearance of the whole of a product per se does not provide protection (also) only for a part. If the holder seeks establishing such a partial protection, he is permitted to do that by making a specific claim to a part of a product which is permitted under Article 3 lit a CDR according to which “design” means “the appearance of the whole or a part of a product”.

Remarks

The denial of partial protection was in dispute at least in Germany for many years amongst Appeal Courts such as those in Munich, Hamburg, Hamm and Frankfurt. Now there is clarity in Germany, also in terms of filing strategies – if you wish to claim partial protection you have to file corresponding partial designs.

Interestingly, the Court analyses the case both according to Community design and German design law, even though no protection under German design law was claimed. This also closes any argument that under German design law the result might be different.

Plant Variety Law

Reported by Professor Dr. Alexander von Mühlendahl, J.D., LL.M.

On September 19, 2012, the General Court of the European Union (GC) delivered its decision in four joined cases confronting Mr. Schräder, a plant breeder, and the Community Plant Variety Office (CPVO), the European Union’s agency responsible for administering the Union’s plant variety protection scheme. Mr. Hansson, a breeder from Denmark, was the intervening party. The decision is significant because it confirms the limited scope of review of CPVO decisions, while also confirming the importance of procedural rules.

Hansson is proprietor of Community plant variety rights in a variety of the species Osteospermum ecklonis, a kind of daisy, named LEMON SYMPHONY granted in 1999. Schräder applied for protection of a similar variety, SUMOST 01. The CPVO rejected the Schräder application, having concluded that SUMOST 01 was not distinct from LEMON SYMPHONY. Schräder appealed the decision to the CPVO’s Board of Appeal. Schräder also requested that the rights in LEMON SYMPHONY be declared invalid as having been improperly granted, and that the rights should be revoked because the variety was no longer stable. Schräder also claimed that the variety description for LEMON SYMPHONY, adapted by the CPVO in the course of the proceedings, should be declared invalid. All proceedings eventually reached the Board of Appeal, the CPVO having ruled in favour of the validity of LEMON SYMPHONY and the adaptation of the description. The alleged invalidity of LEMON SYMPHONY reached the Board in January 2009, whereas the other three cases were dealt with by the Board in December 2007.

As regards the validity of LEMON SYMPHONY, subject of Case T-242/09, Mr Schräder alleged, inter alia, that the CPVO and the German Bundessortenamt (Federal Plant Variety Office) had not properly examined the submitted samples prior to grant. As regards the other three cases, a series of procedural violations were alleged, in addition to the violation of rules of substantive law. The principal violation alleged was the Board having summoned for the oral hearing in December 2007 against the protest of Schräder and without observing the statutory period of two months prior to the hearing.

The General Court confirmed the Board decision as regards the validity of LEMON SYMPHONY, but annulled the other three decisions because of the violation of the procedural rights of the claimant as regards the oral hearing held in December 2007.

As regards the validity of LEMON SYMPHONY, the Court first established that in invalidity actions based on Article 20 of the Community Plant Variety Regulation (Council Regulation [EC] No 2100/94 of July 27, 1994 on Community plant variety rights, OJ 1994 L 227, p. 1) the burden of proof as regards invalidity is placed on the party claiming invalidity (emphasis added):

128 The task of the Board of Appeal is solely to rule, on the application of an interested party, on the lawfulness of a decision of the CPVO adopted under Article 20 (1) (a) of the regulation refusing to declare the Community plant variety right null and void on the ground that it has not been ‘established’ by that party that the conditions set out in Article 7 or in Article 10 of that regulation were not satisfied at the time when the right was granted.

129 Since annulment proceedings were initiated not by the CPVO of its own motion, but on the application of an interested party, Articles 76 and 81 of the regulation, read in conjunction with Article 20 thereof, thereby place the onus on that party to prove that the conditions for that declaration of nullity have been met.

Next, as regards the substance of the CPVO’s decision concerning the requirements for plant variety protection – distinctness, uniformity, stability (DUS) – the Court limited its examining by inquiring only whether the Office had committed any manifest errors of assessment:

142 In this connection, it is therefore necessary to make a distinction depending on whether or not the findings and factual assessments made by the Board of Appeal are the result of complex assessments in the botanical or genetics field, requiring expert or specific scientific or technical knowledge (emphasis added).

143 If that is so, the review which, according to case-law, it is for the General Court to carry out of such findings and factual assessments is that as to manifest errors of assessment (Case T-187/06 – Schräder v CPVO [SUMCOL 01] [2008] ECR II 3151, paragraphs 59 to 53, essentially confirmed on appeal by the judgment in Case C 38/09 P – Schräder v CPVO [2010] ECR I 3209, paragraph 77). That is true, for example, of the assessment of the distinctive character of a variety, in the light of the criteria set out in Article 7 (1) of the regulation.

144 If that is not so, on the other hand, as regards factual assessments which are not of a specific technical or scientific complexity, it is apparent from that case law that the General Court carries out a complete or full review of legality (SUMCOL 01, paragraph 65, and Case

C- 38/09 P Schräder v CPVO, paragraph 77).

The Court found that the contested decision was not erroneous.

As regards the other three cases, the Court annulled the contested decision because the Board had violated the claimant’s rights by holding the hearing on December 4, 2007 against his express protests and having summoned the claimant to the hearing without observing the statutory notice period of two months.

We report this judgment of the General Court for essentially two reasons, while we generally do not report judgments of the General Court, which in trade mark cases reach 200 per year.

First, decisions of the General Court, and even more so of the Court of Justice of the European Union (ECJ) in plant variety matters are rare, even though the economic significance of plant variety rights is far from marginal. Thus, the Community Plant Variety Office, located in Angers, France, began operations in 1996, and currently close to 19.000 plant variety rights are in force, in the fields of agriculture, vegetables, ornamentals, and fruits.

Remarks

Appeals against the CPVO’s Board of Appeal to the General Court and further appeals on points of law are rare – the only case having reached the ECJ so far is the SUMCOL 01 case, referred to in paragraph 143 of the present decision, quoted above.

Second, the approach of the General Court to the examination of CPVO decisions, confirmed by the ECJ, distinguished between questions requiring technical expertise, such as determinations as to the DUS criteria, and those not requiring such expertise. In the former situations the Court will limit itself to determining whether there have been any manifest errors of appreciation (not present in the contested decisions subject to the reported judgment). In the latter situations the Court will do a full examination as to any errors committed. It is noteworthy that this approach differs from that taken by the Court in cases of reviewing decisions of the Boards of Appeal of OHIM, the European Union’s Trade Marks and Designs Office. The scope or “depth” of review of OHIM decisions in design matters is currently before the ECJ (Case C-102/11 P).

BARDEHLE PAGENBERG represented the CPVO in these cases.